Quilt

A quilt is a multi-layered textile, traditionally composed of two or more layers of fabric or fiber. Commonly three layers are used with a filler material. These layers traditionally include a woven cloth top, a layer of batting or wadding, and a woven back combined using the techniques of quilting. This is the process of sewing on the face of the fabric, and not just the edges, to combine the three layers together to reinforce the material. Stitching patterns can be a decorative element. A single piece of fabric can be used for the top of a quilt (a "whole-cloth quilt"), but in many cases the top is created from smaller fabric pieces joined, or patchwork. The pattern and color of these pieces creates the design. Quilts may contain valuable historical information about their creators, "visualizing particular segments of history in tangible, textured ways".[2]

In the twenty-first century, quilts are frequently displayed as non-utilitarian works of art[3] but historically quilts were often used as bedcovers; and this use persists today.

(In modern English, the word "quilt" can also be used to refer to an unquilted duvet or comforter.)

Uses

[edit]

There are many traditions regarding the uses of quilts. Quilts may be made or given to mark important life events such as marriage, the birth of a child, a family member leaving home, or graduations. Modern quilts are not always intended for use as bedding, and may be used as wall hangings, table runners, or tablecloths. Quilting techniques are often incorporated into garment design as well. Quilt shows and competitions are held locally, regionally, and nationally. There are international competitions as well, particularly in the United States, Japan, and Europe.

The following list summarizes most of the reasons a person might decide to make a quilt:

- Bedding

- Decoration

- Armor (e.g., the garment called a gambeson)

- Commemoration (e.g., the AIDS Memorial Quilt)

- Education (e.g., a "Science" quilt or a "Gardening" quilt)

- Campaigning

- Documenting events / social history, etc.

- Artistic expression (e.g., Quilt art)

- Gift

- Fundraiser

Traditions

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2017) |

Quilting traditions are particularly prominent in the United States, where the necessity of creating warm bedding met the paucity of local fabrics in the early days of the colonies. Imported fabric was very expensive, and local homespun fabric was labor-intensive to create and tended to wear out sooner than commercial fabric. It was essential for most families to use and preserve textiles efficiently. Saving or salvaging small scraps of fabric was a part of life for all households. Small pieces of fabric were joined to make larger pieces, in units called "blocks". Creativity could be expressed in the block designs, or simple "utility quilts", with minimal decorative value, could be produced. Crib quilts for infants were needed in the cold of winter, but even early examples of baby quilts indicate the efforts that women made to welcome a new baby.

Quilting was often a communal activity, involving all the women and girls in a family or in a larger community. There are also many historical examples of men participating in these quilting traditions.[4] The tops were prepared in advance, and a quilting bee was arranged, during which the actual quilting was completed by multiple people. Quilting frames were often used to stretch the quilt layers and maintain even tension to produce high-quality quilting stitches and to allow many individual quilters to work on a single quilt at one time. Quilting bees were important social events in many communities, and were typically held between periods of high demand for farm labor. Quilts were frequently made to commemorate major life events, such as marriages.

Quilts were often made for other events as well, such as graduations, or when individuals left their homes for other communities. One example of this is the quilts made as farewell gifts for pastors; some of these gifts were subscription quilts. For a subscription quilt, community members would pay to have their names embroidered on the quilt top, and the proceeds would be given to the departing minister. Sometimes the quilts were auctioned off to raise additional money, and the quilt might be donated back to the minister by the winner. A logical extension of this tradition led to quilts being made to raise money for other community projects, such as recovery from a flood or natural disaster, and later, for fundraising for war. Subscription quilts were made for all of America's wars. In a new tradition, quilt makers across the United States have been making quilts for wounded veterans of the Afghanistan and Iraq conflicts.

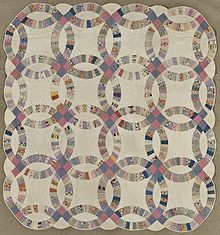

There are many American traditions regarding the number of quilts a young woman (and her family) was expected to have made prior to her wedding for the establishment of her new home. Given the demands on a new wife, and the learning curve in her new role, it was prudent to provide her some reserve time with quilts already completed. Specific wedding quilts continue to be made today. Wedding ring quilts, which have a patchwork design of interlocking rings, have been made since the 1930s. White wholecloth quilts with high-quality, elaborate quilting, and often trapunto decorations as well, are also traditional for weddings. A superstition existed that it was bad luck to incorporate heart motifs in a wedding quilt (the couples’ hearts might be broken if such a design were included), so tulip motifs were often used to symbolize love in wedding quilts.

The Museum of the Southern Jewish Experience in New Orleans holds a 19th-century exemplar of a "crazy quilt" (one without a pattern) "that was made by the Jewish Ladies’ Sewing Club of Canton, Miss., in 1885 to be raffled off to help fund the building of a synagogue there".[5] (A photo of this quilt accompanies this citation.) The Museum's director, Kenneth Hoffman, says that this quilt involves "lots of little pieces that come together to make something greater than the sum of its parts, it’s crazy but it’s beautiful, it has a social aspect of ladies sitting together sewing, it has a religious aspect."[5]

William Rush Dunton (1868–1966), psychiatrist, collector, and scholar of American quilts incorporated quilting as part of his occupational therapy treatment. "Dr Dunton, the founder of the American Occupational Therapy Association, encouraged his patients to pursue quilting as a curative activity/therapeutic diversion...."[4]

The National Quilt Museum is in Paducah, Kentucky, in the Southern United States. It hosts QuiltWeek, an annual competition and celebration of that attracts artists and hobbyists from the world of quilting.[6] QuiltWeek has been celebrated in a short documentary by Olivia Loomis Merrion called Quilt Fever. It explores what quilting means to its practitioners along with what it means to Paducah, which has earned the nickname "Quilt City, USA".[7]

Among the many television programs as well as YouTube channels devoted to quilting, Love of Quilting, which originates in a magazine of the same name, stands out for being aired on PBS.[8]

Techniques

[edit]Patchwork and piecing

[edit]One of the primary techniques involved in quilt making is patchwork, sewing together geometric pieces of fabric often to form a design or "block". Also called piecing, this technique can be achieved with hand stitching or with a sewing machine.[9]

Appliqué

[edit]

Appliqué is a sewing technique where an upper layer of fabric is sewn onto a ground fabric. The upper, applied fabric shape can be of any shape or contour. There are several different appliqué techniques and styles. In needle-turn appliqué, the raw edges of the appliquéd fabric are tucked beneath the design to minimize raveling or damage, and small hand stitches are made to secure down the design. The stitches are made with a hem stitch, so that the thread securing the fabric is minimally visible from the front of the work. There are other methods to secure the raw edge of the appliquéd fabric, and some people use basting stitches, fabric-safe glue, freezer paper, paper forms, or starching techniques to prepare the fabric that will be applied, prior to sewing it on. Supporting paper or other materials are typically removed after the sewing is complete. The ground fabric is often cut away from behind, after the sewing is complete, to minimize the bulk of the fabric in that region. A special form of appliqué is Broderie perse, which involves the appliqué of specific motifs that have been selected from a printed fabric. For example, a series of flower designs might be cut out of one fabric with a vine design, rearranged, and sewn down on a new fabric to create the image of a rose bush.

Reverse appliqué

[edit]Reverse appliqué is a sewing technique where a ground fabric is cut, another piece of fabric is placed under the ground fabric, the raw edges of the ground fabric are tucked under, and the newly folded edge is sewn down to the lower fabric. Stitches are made as inconspicuous as possible. Reverse appliqué techniques are often used in combination with traditional appliqué techniques, to give a variety of visual effects.

Quilting

[edit]A key component that defines a quilt is the stitches holding the three layers together—the quilting. Quilting, typically a running stitch, can be achieved by hand or by sewing machine. Hand quilting has often been a communally productive act with quilters sitting around a large quilting frame. One can also hand quilt with a hoop or other method. With the development of the sewing machine, some quilters began to use the sewing machine, and in more recent decades machine quilting has become quite commonplace, including with longarm quilting machines.[10]

Trapunto

[edit]Trapunto is a sewing technique where two layers of fabric surrounding a layer of batting are quilted together, and then additional material is added to a portion of the design to increase the profile of relief as compared to the rest of the work. The effect of the elevation of one portion is often heightened by closely quilting the surrounding region, to compress the batting layer in that part of the quilt, thus receding the background even further. Cording techniques may also be used, where a channel is created by quilting, and a cord or yarn is pulled through the batting layer, causing a sharp change in the texture of the quilt. For example, several pockets may be quilted in the pattern of a flower, and then extra batting pushed through a slit in the backing fabric (which will later be sewn shut). The stem of the rose might be corded, creating a dimensional effect. The background could be quilted densely in a stipple pattern, causing the space around the rose bush to become less prominent. These techniques are typically executed with wholecloth quilts, and with batting and thread that matches the top fabric. Some artists have used contrasting colored thread, to create an outline effect. Colored batting behind the surface layer can create a shadowed effect. Brightly colored yarn cording behind white cloth can give a pastel effect on the surface.

Embellishment

[edit]Additional decorative elements may be added to the surface of a quilt to create a three-dimensional or whimsical effect. The most common objects sewn on are beads or buttons. Decorative trim, piping, sequins, found objects, or other items can also be secured to the surface. The topic of embellishment is explored further on another page.

English paper piecing

[edit]

English paper piecing is a hand-sewing technique used to maximize accuracy when piecing complex angles together. A paper shape is cut with the exact dimensions of the desired piece. Fabric is then basted to the paper shape. Adjacent units are then placed face to face, and the seam is whipstitched together. When a given piece is completely surrounded by all the adjacent shapes, the basting thread is cut, and the basting and the paper shape are removed.

Foundation piecing

[edit]Foundation piecing is a sewing technique that allows maximum stability of the work as the piecing is created, minimizing the distorting effect of working with slender pieces or bias-cut pieces. In the most basic form of foundation piecing, a piece of paper is cut to the size of the desired block. For utility quilts, a sheet of newspaper was used. In modern foundation piecing, there are many commercially available foundation papers. A strip of fabric or a fabric scrap is sewn by machine to the foundation. The fabric is flipped back and pressed. The next piece of fabric is sewn through the initial piece and its foundation paper. Subsequent pieces are added sequentially. The block may be trimmed flush with the border of the foundation. After the blocks are sewn together, the paper is removed, unless the foundation is an acid-free material that will not damage the quilt over time.

Intarsia

[edit]Rarer and less well-known are quilts made by men in a military setting. They are made of broadcloth which is cut into elements abutting each other as intarsia and then over-sewn. Front and back of the work are in principle identical and the quilts reversible, except in cases where elements of appliqué, embroidery or trapunto have been added on the front, which is quite common in more elaborate or illustrative pieces.[11][12]

Quilting styles

[edit]North America

[edit]Amish

[edit]

Amish quilts are reflections of the Amish way of life. As a part of their religious commitment, Amish people have chosen to reject "worldly" elements in their dress and lifestyle, and their quilts historically reflected this, although today Amish make and use quilts in a variety of styles.[13] Traditionally, the Amish use only solid colors in their clothing and the quilts they intend for their own use, in community-sanctioned colors and styles. In Lancaster, Pennsylvania, early Amish quilts were typically made of solid-colored, lightweight wool fabric, off the same bolts of fabric used for family clothing items, while in many Midwestern communities, cotton predominated. Classic Amish quilts often feature quilting patterns that contrast with the plain background. Antique Amish quilts are among the most highly prized by collectors and quilting enthusiasts. The color combinations used in a quilt can help experts determine the community in which the quilt was produced. Since the 1970s, Amish quiltmakers have made quilts for the consumer market, with quilt cottage industries and retail shops appearing in Amish settlements across North America.[13]

Baltimore album

[edit]Baltimore album quilts originated in the region around Baltimore, Maryland, in the 1840s, where a unique and highly developed style of appliqué quilting briefly flourished. Baltimore album quilts are variations on album quilts, which are collections of appliquéd blocks, each with a different design. These designs often feature floral patterns, but many other motifs are used as well. Baskets of flowers, wreaths, buildings, books, and birds are common motifs. Designs are often highly detailed, and display the quiltmaker's skill. New dyeing techniques became available in this period, allowing the creation of new, bold colors, which the quilters used enthusiastically. New techniques for printing on the fabrics also allowed portions of fabric to be shaded, which heightens the three-dimensional effect of the designs. The background fabric is typically white or off-white, allowing maximal contrast to the delicate designs. India ink allowed handwritten accents and also allowed the blocks to be signed. Some of these quilts were created by professional quilters, and patrons could commission quilts made of new blocks, or select blocks that were already available for sale. There has been a resurgence of quilting in the Baltimore style, with many of the modern quilts experimenting with bending some of the old rules.

Crazy quilts

[edit]Crazy quilts are so named because their pieces are not regular, and they are scattered across the top of the quilt like "crazed" (cracked or crackled) pottery glazing. They were originally very refined, luxury items. Geometric pieces of rich fabrics were sewn together, and highly decorative embroidery was added. Such quilts were often effectively samplers of embroidery stitches and techniques, displaying the development of needle skills of those in the well-to-do late 19th-century home. They were show pieces, not used for warmth, but for display. The luxury fabrics used precluded frequent washing. They often took years to complete. Fabrics used included silks, wools, velvet, linen, and cotton. The mixture of fabric textures, such as a smooth silk next to a textured brocade or velvet, was embraced. Designs were applied to the surface, and other elements such as ribbons, lace, and decorative cording were used exuberantly. Names and dates were often part of the design, added to commemorate important events or associations of the maker. Politics were included in some, with printed campaign handkerchiefs and other preprinted textiles (such as advertising silks) included to declare the maker's sentiments.

African-American

[edit]

By the time that early African-American quilting became a tradition in and of itself, it was already a combination of textile traditions from four civilizations of Central and West Africa: the Mande-speaking peoples, the Yoruba and Fon peoples, the Ejagham peoples, and the Kongo peoples.[14][15] As textiles were traded heavily throughout the Caribbean, Central America, and the Southern United States, the traditions of each distinct region became intermixed. Originally, most of the textiles were made by men. Yet when enslaved Africans were brought to the United States, their work was divided according to traditional Western gender roles and women took over the tradition. However, this strong tradition of weaving left a visible mark on African-American quilting. The use of strips, reminiscent of the strips of reed and fabric used in men's traditional weaving, are used in fabric quilting. A break in a pattern symbolized a rebirth in the ancestral power of the creator or wearer. It also helped keep evil spirits away; evil is believed to travel in straight lines and a break in a pattern or line confuses the spirits and slows them down. This tradition is highly recognizable in African-American improvisations on European-American patterns. The traditions of improvisation and multiple patterning also protect the quilter from anyone copying their quilts. These traditions allow for a strong sense of ownership and creativity.[16]

In the 1980s, concurrent with the boom in art quilting in America, new attention was brought to African-American traditions and innovations. This attention came from two opposing points of view, one validating the practices of rural Southern African-American quilters and another asserting that there was no one style but rather the same individualization found among white quilters.[17] John Vlach, in a 1976 exhibition, and Maude Wahlman, co-organizing a 1979 exhibition, both cited the use of strips, high-contrast colors, large design elements, and multiple patterns as characteristic and compared them to rhythms in black music.[18] Building on the relationship between quilting and musical performance, African-American quilter Gwendolyn Ann Magee created a twelve-piece exhibition based on the lyrics of James Weldon Johnson's "Lift Every Voice and Sing", commonly known as the "Negro National Anthem".[19] Cuesta Benberry, a quilt historian with a special interest in African-American works, published Always There: The African-American Presence in American Quilts in 1992 and organized an exhibition documenting the contributions of black quilters to mainstream American quilting.[20] Eli Leon, a collector of African-American quilts, organized a traveling exhibition in 1987 that introduced both historic and current quilters, some loosely following patterns and others improvising, such as Rosie Lee Tompkins. He argued for the creativity of the irregular quilt, saying that these quilters saw the quilt block as "an invitation to variation" and felt that measuring "takes the heart outa things".[21] At the same time, the Williams College Museum of Art was circulating Stitching Memories: African-American Story Quilts, an exhibition featuring a different approach to quilts, including most prominently the quilts of Faith Ringgold. However, it was not until 2002, when the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, organized The Quilts of Gee's Bend, an exhibition that appeared in major museums around the country, including the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, that art critics unknowingly adopted Leon's assertions.[22]

Story quilts

[edit]Story quilts have much in common with pictorial quilts and the tradition of African-American quiltmakers and are often made as a form of quilt art. Usually adorned with extensive text and accompanying imagery, story quilts can contain short stories, poems, or extended essays and can be used as an alternative form of a picture book.[23] Artist Faith Ringgold, known for her large portfolio of story quilts, has said she began making these narrative quilts with extensive text after being unable to find a publisher that would accept her autobiography. She began quilting so that "when my quilts were hung up to look at, or photographed for a book, people could still read my stories".[24]

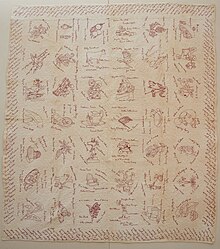

Pictorial quilts

[edit]Pictorial quilts often contain one-of-a-kind patterns and imagery. Instead of bringing together fabric in an abstract or patterned design, they use pieces of fabric to create objects on the quilt, resulting in a picture-based quilt. They were often made collaboratively as a fundraising effort. However, some pictorial quilts were individually created and tell a narrative through the images on the quilt. Some pictorial quilts consist of many squares, sometimes made by multiple people, while others have imagery that uses the entirety of quilt. Pictorial quilts were created in the United States, as well as in England and Ireland, beginning as early as 1795.[25][26]

-

Pictorial Quilt, 1795. Linen, multicolored thread. Brooklyn Museum

-

American. Pictorial Quilt, ca. 1840. Cotton, cotton thread. Brooklyn Museum

Barn quilts

[edit]Barn quilts are a type of folk art found in the United States (particularly the South and Midwest) and Canada. They take the patterns of traditional quilt squares, and recreate them either directly on the side of a barn or on a piece of wood or aluminum which is then attached to the side of a barn.[27] Patterns are sometimes modeled off of family quilts, loved ones, patriotic themes, or important crops to the farm.[28] The origins of the barn quilt are contested- some claim they date back almost 300 years, but some claim they were invented by Donna Sue Groves of Adams County, Ohio in 2001.[29] Their origin is likely connected to barn advertisements. Many rural counties will display their barn quilts as part of a quilt trail, creating a route that connects barns with barn quilts to sponsor local tourism.

Hawaiian

[edit]Hawaiian quilts are wholecloth (not pieced) quilts, featuring large-scale symmetrical appliqué in solid colors on a solid color (usually white) background fabric. Traditionally, the quilter would fold a square piece of fabric into quarters or eighths and then cut out a border design, followed by a center design. The cutouts would then be appliquéd onto a contrasting background fabric. The center and border designs were typically inspired by local flora and often had rich personal associations for the creator, with deep cultural resonances. The most common color for the appliquéd design was red, due to the wide availability of Turkey-red fabric.[30] Some of these textiles were not in fact quilted but were used as decorative coverings without the heavier batting, which was not needed in a tropical climate. Multiple colors were added over time as the tradition developed. Echo quilting, where a quilted outline of the appliqué pattern is repeated like ripples out to the edge of the quilt, is the most common quilting pattern employed on Hawaiian-style quilts. Beautiful examples are held in the collection of the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum, Honolulu, Hawaii.

-

Group of people from Niʻihau with their quilt, 1885

-

Kuʻu Hae Aloha (My Beloved Flag), from Waimea, before 1918, Honolulu Museum of Art

-

Kapa Kuiki

Native American star quilts

[edit]Star Quilts are a Native-American form of quilting that arose among native women in the late 19th century as communities adjusted to the difficulties of reservation life and cultural disruption. They are made by many tribes, but came to be especially associated with Plains tribes, including the Lakota. While star patterns existed in earlier European-American forms of quilting, they came to take on special significance for many native artisans.[31] Star quilts are more than an art form—they express important cultural and spiritual values of the native women who make them and continue to be used in ceremonies and to mark important points in a person's life, including curing or yuwipi ceremonies and memorials. Anthropologists (such as Bea Medicine) have documented important social and cultural connections between quilting and earlier important pre-reservation crafting traditions, such as women's quill-working societies[32] and other crafts that were difficult to sustain after hunting and off-reservation travel was restricted by the US government. Star quilts have also become a source of income for many Native-American women, while retaining spiritual and cultural importance to their makers.

Seminole patchwork

[edit]

Created by the Native Americans of southern Florida, Seminole strip piecing is based on a simple form of decorative patchwork. Seminole strip piecing has uses in quilts, wall hangings, and traditional clothing. Seminole patchwork is created by joining a series of horizontal strips to produce repetitive geometric designs.

Europe

[edit]The history of quilting in Europe goes back at least to Medieval times. Quilting was used not only for traditional bedding but also for warm clothing. Clothing quilted with fancy fabrics and threads was often a sign of nobility.

British quilts

[edit]Henry VIII of England's household inventories record dozens of "quyltes" and "coverpointes" among the bed linen, including a green silk one for his first wedding to Catherine of Aragon, quilted with metal threads, linen-backed, and worked with roses and pomegranates.[33]

An embroidered yellow silk quilt from Bengal dating from the 1620s, an early example of such fabric use in Britain, now held by the Colonial Williamsburg museum, has an ownership label of Catherine Colepeper, connecting it to Leeds Castle and the Smythe and Colepeper families. Thomas Smythe, a brother of the owner of Leeds Castle, was a founder and governor of the English East India Company.[34]

Otherwise known as Durham quilts, North Country quilts have a long history in northeastern England, dating back to the Industrial Revolution and beyond. North Country quilts are often wholecloth quilts, featuring dense quilting. Some are made of sateen fabrics, which further heightens the effect of the quilting.

From the late 18th to the early 20th century, the Lancashire cotton industry produced quilts using a mechanized technique of weaving double cloth with an enclosed heavy cording weft, imitating the corded Provençal quilts made in Marseilles.[citation needed]

Italian quilts

[edit]Quilting was particularly common in Italy during the Renaissance. One particularly famous surviving example, now in two parts, is the 1360–1400 Tristan Quilt, a Sicilian-quilted linen textile representing scenes from the story of Tristan and Isolde and housed in the Victoria and Albert Museum and in the Bargello in Florence.[35]

Provençal quilts

[edit]

Provençal quilts, now often referred to as "boutis" (the Provençal word meaning "stuffing"), are wholecloth quilts traditionally made in the South of France since the 17th century. Two layers of fabric are quilted together with stuffing sandwiched between sections of the design, creating a raised effect.[36] The three main forms of the Provençal quilt are matelassage (a double-layered wholecloth quilt with batting sandwiched between), corded quilting or piqûre de Marseille (also known as Marseilles work or piqué marseillais), and boutis.[36] These terms are often debated and confused, but are all forms of stuffed quilting associated with the region.[36]

Asia

[edit]China

[edit]

Throughout China, a simple method of producing quilts is employed. It involves setting up a temporary site. At the site, a frame is assembled within which a lattice work of cotton thread is made. Cotton batting, either new or retrieved from discarded quilts, is prepared in a mobile carding machine. The mechanism of the carding machine is powered by a small, petrol motor. The batting is then added, layer by layer, to the area within the frame. Between adjacent layers, a new lattice of thread is created with a wooden disk used to tamp down the layer. (See: Image series showing production method)

Japan: Sashiko

[edit]Sashiko (刺し子, literally "little stabs") is a Japanese tradition that evolved over time from a simple technique for reinforcing fabric made for heavy use in fishing villages. It is a form of decorative stitching, with no overlap of any two stitches. Piecing is not part of the tradition; instead, the focus is on heavy cotton thread work with large, even stitches on the base fabric. Deep blue indigo-dyed fabric with white stitches is the most traditional form, but inverse work with blue on white is also seen. Traditional medallion, tessellated, and geometric designs are the most common.

Bangladeshi quilts

[edit]

Bangladeshi quilts, known as Kantha, are not pieced together. Rather, they consist of two to three pieces of cloth sewn together with decorative embroidery stitches. They are made out of worn-out clothes (saris) and are mainly used for bedding, although they may be used as a decorative piece as well. They are made by women mainly in the Monsoon season before winter.

India: Kantha, Ralli, and Balaposh — the unquilted scented quilt

[edit]

Women in the Indus Region of the Indian subcontinent make beautiful quilts with bright colors and bold patterns. The quilts are called "Ralli" (or rilli, rilly, rallee, or rehli) derived from the local word "ralanna" meaning to mix or connect. Rallis are made in the southern provinces of Pakistan including Sindh, Baluchistan, and in the Cholistan Desert on the southern border of Punjab, as well as in the adjoining states of Gujarat and Rajasthan in India. In India Kantha originated from the Sanskrit word kontha, which means rags, as the blankets are made out of rags[37] using different scrap pieces of cloth. Nakshi kantha consisting of a running (embroidery) stitch, similar to the Japanese Sashiko is used for decorating and reinforcing the cloth and sewing patterns. Katab work called in Kutch. It is popularly known as Koudhi in Karnataka. Such blankets are given as gifts to newborn babies in many parts of India. Lambani tribes wear skirts with such art. Muslim and Hindu women from a variety of tribes and castes in towns, villages, and also nomadic settings make rallis. Quiltmaking is an old tradition in the region perhaps dating back to the fourth millennium BC, judging by similar patterns found on ancient pottery. Jaipuri razai (quilt) is one of the most famous things in Jaipur because of the traditional art and process of making it. Jaipuri razai is printed by the process of Screen printing or block printing which are both handmade processes carried out by the local artisans of Jaipur, Sanganer, and Bagru. Jaipuri quilts are designed to keep you warm during winters without irritating your skin. By including elements of traditional art in your modern living spaces, you can preserve the essence of Indian culture wherever you live.

Rallis are commonly used as a covering for wooden sleeping cots, as a floor covering, storage bag, or padding for workers or animals. In the villages, ralli quilts are an important part of a girl's dowry. Owning many ralli quilts is a measure of wealth. Parents present rallis to their daughters on their wedding day as a dowry.

Rallis are made from scraps of cotton fabric dyed to the desired color. The most common colors are white, black, red, and yellow or orange with green, dark blue, or purple. For the bottoms of the rallis, the women use old pieces of tie-dye, ajrak, or other shawl fabric. Ralli quilts have a few layers of worn fabric or cotton fibers between the top and bottom layers. The layers are held together by thick colored thread stitched in straight lines. The women sit on the ground and do not use a quilting frame. Another kind of ralli quilt is the sami ralli, used by the samis and jogis. This type of ralli quilt is popular due to the many colors and the extensive hand-stitching employed in its construction.

The number of patterns used on ralli quilts seems to be almost endless, as there is much individual expression and spontaneity in color within the traditional patterns. The three basic styles of rallis are: 1) patchwork quilts made from pieces of cloth torn into squares and triangles and then stitched together, 2) appliqué quilts made from intricate cut-out patterns in a variety of shapes, and 3) embroidered quilts where the embroidery stitches form patterns on solid colored fabric.

A distinguishing feature of ralli patterning in patchwork and appliqué quilts is the diagonal placement of similar blocks as well as a variety of embellishments including mirrors, tassels, shells, and embroidery.[38]

Rural women in the Uttara Kannada region of India carry out traditional quilting practices that are interwoven with rituals around food availability and access. Primarily made in Yadgir, Bagalkot, Gulbarga, Angadibail and Haliyal, Kavudis are handmade patchwork quilts with around multiple layers including the batting or insulation.[39]

Africa, Oceania and South America

[edit]Cook Islands: Tivaevae quilts

[edit]Tivaevae are quilts made by Cook Island women for ceremonial occasions. Quilting is thought to have been imported to the Islands by missionaries. The quilts are highly prized and are given as gifts with other finely made works on important occasions such as weddings and christenings.

Egyptian khayamiya

[edit]Khayamiya is a form of suspended tent decoration or portable textile screen used across North Africa and the Middle East. It is an art form distinctive to Egypt, where they are still sewn by hand in the Street of the Tentmakers (Sharia Khayamiya) in Cairo. Whilst Khayamiya resemble quilts, they typically possess a heavy back layer and fine top layer of appliqué, without a central insulating layer.

Kuna: Mola textiles

[edit]

Mola textiles are a distinct tradition created by the Kuna people of Panama and Colombia. They are famous for their bright colors and reverse appliqué techniques, which create designs with strong cultural and spiritual importance within the indigenous culture. Forms of animals, humans, or mythological figures are featured, with strong geometric designs in the voids around the main image. These textiles are not traditionally used as bedding, but use techniques common to the larger international quilting tradition. Molas have been very influential on modern quilting design.

Block designs

[edit]

There are many traditional block designs and techniques that have been named.

- Log cabin quilts are pieced quilts featuring blocks made of strips of fabric, typically encircling a small centered square (traditionally a red square, symbolizing the hearth of the home), with light strips forming half the square and dark strips the other half. Dramatic contrast effects with light and dark fabrics are created by various layouts of the blocks when joined to form a quilt top. These different layout variations are often named; some layouts include Sunshine and Shadow, Straight Furrows, Streak of Lightning, and Barn Raising.

- Nine-patch blocks are often the first blocks a child is taught to make. The block consists of three rows of three squares. A checkerboard effect with alternating dark and light squares is most commonly used.

- The double wedding ring pattern first came to prominence during the Great Depression. The design consists of interlocking circles pieced with small arcs of fabric. The finished quilts are often given to commemorate marriages.

- Cathedral windows is a type of block that features reverse appliqué using large amounts of folded muslin, and consists of modular blocks in an interlocking circular design that frame small squares or diamonds of colorful lightweight cotton. The volume of fabric is high, and the tops are heavy. Because of the weight and the insulating value of the base fabric, these tops often are assembled without batting (and thus need no quilting stitches), and sometimes have no backing. Such a quilt may be called a "counterpane" and may serve mainly as a decorative bedspread.

Quilting technique

[edit]Quilts on display

[edit]One of the most famous quilts in history is the AIDS Memorial Quilt, which was begun in San Francisco in 1987, and is cared for by The NAMES Project Foundation. Portions of it are periodically displayed in various arranged locations. Panels are made to memorialize a person lost to HIV, and each block is 3 feet by 6 feet. Many of the blocks are not made by traditional quilters, and the amateur creators may lack technical skill, but their blocks speak directly to the love and loss they have experienced. The blocks are not in fact quilted, as there is no stitching holding together batting and backing layers. Exuberant designs, with personal objects applied, are seen next to restrained and elegant designs. Each block is very personal, and they form a deeply moving sight when combined by the dozens and the hundreds. The quilt as a whole is still under construction, although the entire quilt is now so large that it cannot be assembled in complete form in any one location.

Beginning with the Whitney Museum of American Art's 1971 exhibit, Abstract Design in American Quilts, quilts have frequently appeared on museum and gallery walls. The exhibit displayed quilts like paintings on its gallery walls, which has since become a standard way to exhibit quilts. The Whitney exhibit helped shift the perception of quilts from solely a domestic craft object to art objects, increasing art world interest in them.[40]

The National Quilt Museum is located in Paducah, Kentucky. The museum houses a large collection of contemporary quilts, and features approximately a dozen exhibitions each year showcasing the works of "today's quilters" from America and around the world.

In 2010, the world-renowned Victoria and Albert Museum put on a comprehensive display of quilts from 1700 to 2010,[41] while in 2009, the American Folk Art Museum in New York put on an exhibition of the work of kaleidoscope quilt maker Paula Nadelstern, marking the first time that museum has ever offered a solo show to a contemporary quilt artist.[42]

Many historic quilts can be seen in Bath at the American Museum in Britain, and Beamish Museum preserves examples of the North East England quiltmaking tradition.

The largest known public collection of quilts is housed at the International Quilt Study Center & Museum at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln in Lincoln, Nebraska. In 2018 documentary filmmaker Ken Burns' personal collection of quilts was exhibited there.[43]

Examples of Tivaevae[44] and other quilts can be found in the collection of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.

The San Jose Museum of Quilts and Textiles in California also displays traditional and modern quilts. There is free admission to the museum on the first Friday of every month, as part of the San Jose Art Walk.

The New England Quilt Museum is located in Lowell, Massachusetts.

The Rocky Mountain Quilt Museum is located in Golden, Colorado.

Numerous Hawaiian-style quilts can be seen at Bishop Museum, in Honolulu, Hawaii.

In literature

[edit]- Ismat Chughtai wrote an Urdu-language story entitled "Lihaf" ("The Quilt", 1941) that led to scandal and an unsuccessful attempt at legal prosecution of the author because it was about a Lesbian relationship.[citation needed]

- The Quilter's Apprentice and many others by Jennifer Chiaverini

- Alias Grace by Margaret Atwood

- How to Make an American Quilt by Whitney Otto

- A Fine Balance by Rohinton Mistry

- Everyday Use by Alice Walker

- The Keeping Quilt by Patricia Polacco

- The Last Runaway by Tracy Chevalier

See also

[edit]- Conservation and restoration of quilts

- List of quilters

- Mathematics and fiber arts

- Southern AIDS Living Quilt

References

[edit]- ^ "Quilts as Visual History: Introduction". Clio.

- ^ Jennifer Reeder. "Quilts as Visual History: 'Send out an old quilt': Quilts as Homespun War Memorials". Clio Visualizing History. Retrieved May 9, 2024.

- ^ International Quilt Study Center and Museum. "Quilts as Art". World Quilts: The American Story. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- ^ a b Burks, Jean; Cunningham, Joe (2012). Man Made Quilts: Civil War to the Present. Shelburne Museum Inc. pp. 1–26. ISBN 978-0-939384-37-2.

- ^ a b Grisar, PJ (February 14, 2020). "A museum devoted to Southern Jewish culture to open in fall of 2020". Forward. Retrieved February 16, 2020.

- ^ Linda Elisabeth LaPinta, Kentucky Quilts and Quiltmakers: Three Centuries of Creativity, Community, and Commerce (University Press of Kentucky, 2023) online review of this book.

- ^ Roustan, Céline (March 21, 2020). "Quilt Fever". SXSW Shorts. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ "Fons & Porter's Love of Quilting". Quilting Daily. 2020. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- ^ International Quilt Study Center & Museum (2013). "Patchwork". World Quilts: The American Story. Retrieved March 21, 2017.

- ^ International Quilt Study Center & Museum (2013). "Quilting". World Quilts: The American Story. Retrieved March 21, 2017.

- ^ Christopher Allen (April 27, 2024). "Soldiers and sailors quilts attest to long, adventurous careers". The Australian. Retrieved May 9, 2024.

- ^ Gero, Annette (2024). Quilts: The Fabric of War 1760–1900. The Beagle Press. ISBN 978-0947349721.

- ^ a b Smucker, Janneken (2013). Amish Quilts: Crafting an American Icon. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9781421410531.

- ^ Farrington, Lisa (2005). Creating Their Own Image The History of African-American Women Artists. Oxford University Press. pp. 30–31. ISBN 9780195167214.

- ^ Wahlman, Maude (1986). "African Symbolism in Afro-American Quilts". African Arts. 20 (1): 68–76. doi:10.2307/3336568. JSTOR 3336568.

- ^ Maude Southwell Wahlman. Signs and Symbols: African Images in African-American Quilts, Penguin: 1993 ISBN 978-0525936886

- ^ International Quilt Study Center & Museum. "Race". World Quilts: The American Story. Retrieved June 17, 2014.

- ^ Janet Catherine Berlo and Patricia Cox Crews, Wild by Design: Two Hundred Years of Innovation and Artistry in American Quilts, Lincoln, Nebraska, International Quilt Study Center at the University of Nebraska in association with University of Washington Press, 2003, p. 28

- ^ Moye, Dorothy (September 11, 2014). "Lift Every Voice and Sing: The Quilts of Gwendolyn Ann Magee". Southern Spaces. Archived from the original on November 15, 2014. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- ^ Dennis Hevesi, "Cuesta Benberry, 83, Historian of Quilting", The New York Times, September 10, 2007

- ^ Eli Leon, Who'd A Thought It: Improvisation in African-American Quiltmaking, San Francisco: San Francisco Craft and Folk Art Museum, 1987, pp. 25, 30

- ^ Michael Kimmelman, "Jazzy Geometry, Cool Quilters", The New York Times, November 29, 2002; and Richard Kalina, "Gee's Bend Modern", Art in America, October 2003

- ^ Dunn, Margaret M.; Morris, Ann R. (January 1, 1992). "Narrative Quilts and Quilted Narratives: The Art of Faith Ringgold and Alice Walker". Explorations in Ethnic Studies. 15 (1): 27–32. doi:10.1525/ees.1992.15.1.27 (inactive November 1, 2024). S2CID 49555326. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ ""Faith Ringgold: An American Artist" to Open February 2018". Crocker Art Museum. Retrieved April 27, 2022.

- ^ "Collections: Browse Objects: Pictorial Quilt". Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- ^ "Brooklyn Museum: Shop". Brooklyn Museum. Archived from the original on May 23, 2014. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- ^ "What Are Barn Quilts?". Southern Living. Retrieved April 5, 2024.

- ^ "Barn Quilt FAQs". Barn Quilt Info. February 14, 2023. Retrieved April 5, 2024.

- ^ "Barn Quilts – The story". American Barn Quilts. Retrieved April 5, 2024.

- ^ Susanna Pfeffer (1990). Quilt Masterpieces, Outlet Book Company ISBN 0-517-03297-X

- ^ "The Grandest Quilted Star of All". Judy Anne Breneman. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- ^ Beatrice Medicine (1997). "Lakota Star Quilts: Commodity, Ceremony, and Economic Development". In Marsha L. MacDowell; C. Kurt Dewhurst (eds.). To Honor and Comfort: Native American Quilting Traditions. Museum of New Mexico Press and Michigan State University Museum. ISBN 9780890133163.

- ^ Evans, Lisa, History of Medieval & Renaissance Quilting, retrieved June 2, 2010

- ^ Linda Baumgarten and Kimberly Smith Ivey, Four Centuries of Quilts: The Colonial Williamsburg Collection, (Yale, 2014), pp. 16–17.

- ^ The Tristan Quilt in the collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Retrieved February 5, 2010

- ^ a b c Etienne-Bugnot, Isabelle, Quilting in France: The French Traditions, retrieved May 2, 2010

- ^ Zaman, Niaz (1993). The Art of Kantha Embroidery (Second Revised ed.). Dhaka: University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-984-05-1228-7.

- ^ "History of Ralli Quilt". Retrieved July 2, 2017.

- ^ "An entry into the quilt universe". Deccan Herald. August 25, 2022. Retrieved November 16, 2022.

- ^ International Quilt Study Center & Museum. "Abstract Design in American Quilts". World Quilts: The American Story. Retrieved June 17, 2014.

- ^ "Victoria and Albert Museum The world's greatest museum of art and design". Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- ^ Hickman, Pat; Hovey, Gail (May 31, 2009). "Kaleidoscopic Quilts: Paula Nadelstern". American Craft Council.

- ^ "'Uncovered: The Ken Burns Collection' Opens". International Quilt Study Center & Museum. January 8, 2018. Archived from the original on May 3, 2018. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

- ^ "Museum of New Zealand". Retrieved May 20, 2014.

Further reading

[edit]- Carolyn Ducey, "Quilt History Timeline, Pre-History – 1800", International Quilt Study Center & Museum, University of Nebraska–Lincoln

- Celia Eddy, Quilted Planet: A Sourcebook of Quilts from Around the World ISBN 1-4000-5457-5

- LaPinta, Linda Elisabeth. Kentucky Quilts and Quiltmakers: Three Centuries of Creativity, Community, and Commerce (University Press of Kentucky, 2023) online review of this book.

- MacDowell, Marsha, Mary Worrall, Lynne Swanson, and Beth Donaldson. 2016. Quilts and Human Rights. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. 232 pages. ISBN 978-0-8032-4985-1 (soft cover). Online review of the book

- Patricia Ormsby Stoddard (2003). Ralli Quilts: The Traditional Textiles from Pakistan and India, Schiffer ISBN 9780764316975

External links

[edit] Media related to Quilts at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Quilts at Wikimedia Commons- "The Surprisingly Radical History of Quilting", Smithsonian magazine