Hooded Spirits

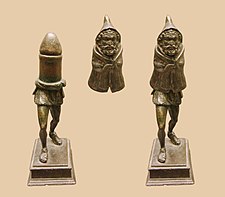

The Hooded Spirits or Genii Cucullati are figures found in religious sculpture across the Romano-Celtic region from Britain to Pannonia, depicted as "cloaked scurrying figures carved in an almost abstract manner".[1] They are found with a particular concentration in the Rhineland (Hutton). In Britain they tend to be found in a triple deity form, which seems to be specific to the British representations.[2]

Name

[edit]The name CucuIlātus is a derivative of Gaulish cucullos, meaning 'hood' (cf. bardo-cucullus 'bard's hood'), whose etymology remains uncertain. Cucullos is the source of Latin cucullus and Old French cogole (via the Latin feminine form cuculla; cf. modern cagoule). The Old Irish cochaIl ('monk's hood'), Cornish cugol, Breton cougoul, and Welsh kwcwIl are loanwords from Latin.[3]

Cult

[edit]

The hooded cape was especially associated with Gauls or Celts during the Roman period. The hooded health god was known as Telesphorus specifically and may have originated as a Greco-Gallic syncretism with the Galatians in Anatolia in the 3rd century BC.[citation needed]

The religious significance of these figures is still somewhat unclear, since no inscriptions have been found with them in this British context.[2] There are, however, indications that they may be fertility spirits of some kind. Ronald Hutton argues that in some cases they are carrying shapes that can be seen as eggs, symbolizing life and rebirth,[4] while Graham Webster has argued that the curved hoods are similar in many ways to contemporary Roman curved phallus stones.[5] However, several of these figures also seem to carry swords or daggers, and Henig discusses them in the context of warrior cults.[1]

Guy de la Bédoyère also warns against reading too much into size differences or natures in the figures, which have been used to promote theories of different roles for the three figures, arguing that at the skill level of most of the carvings, small differences in size are more likely to be hit-or-miss consequences, and pointing out that experimental archaeology has shown hooded figures to be one of the easiest sets of figures to carve.[2]

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b Martin, Henig (1984). Religion in Roman Britain. p. 62. ISBN 0-7134-1220-8.

- ^ a b c de la Bedoyère, Guy (2002). Gods with thunderbolts: Religion in Roman Britain. pp. 166–168. ISBN 0-7524-2518-8.

- ^ Delamarre 2003, p. 131.

- ^ Hutton, Ronald (1991). The Pagan religions of the British isles. pp. 214–216. ISBN 0-631-18946-7.

- ^ Webster, Graham (1986). The British celts and their gods under Rome. pp. 66–70. ISBN 0-7134-0648-8.

Bibliography

[edit]- Delamarre, Xavier (2003). Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise: Une approche linguistique du vieux-celtique continental. Errance. ISBN 9782877723695.

External links

[edit] Media related to Genii cucullati at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Genii cucullati at Wikimedia Commons