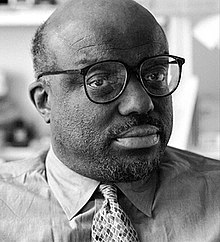

Stanley Crouch

Stanley Crouch | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Stanley Lawrence Crouch December 14, 1945 Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Died | September 16, 2020 (aged 74) New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupations |

|

| Notable work | Don't the Moon Look Lonesome? (2000 novel) |

| Awards | Windham–Campbell Literature Prize (nonfiction), 2016 |

Stanley Lawrence Crouch (December 14, 1945 – September 16, 2020)[1] was an American poet, music and cultural critic, syndicated columnist, novelist, and biographer.[2] He was known for his jazz criticism and his 2000 novel Don't the Moon Look Lonesome?

Biography

[edit]Stanley Lawrence Crouch was born in Los Angeles, the son of James and Emma Bea (Ford) Crouch.[3][4] He was raised by his mother. In Ken Burns' 2005 television documentary Unforgivable Blackness, Crouch said that his father was a "criminal" and that he once met the boxer Jack Johnson. As a child he was a voracious reader, having read the complete works of Ernest Hemingway, Mark Twain, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and many of the other classics of American literature by the time he finished high school. His mother told him of the experiences of her youth in east Texas and the black culture of the southern midwest, including the Kansas City jazz scene. He became an enthusiast for jazz in both the aesthetic and historical senses. He graduated from Thomas Jefferson High School in Los Angeles in 1963. After high school, he attended junior colleges and became active in the civil rights movement, working for the Student Nonviolent Co-ordinating Committee. He was also involved in artistic and educational projects centered on the African-American community of Los Angeles, soon gaining recognition for his poetry. In 1968, he became poet-in-residence at Pitzer College, then taught theatre and literature at Pomona College until 1975. The Watts riots were a pivotal event in his early development as a thinker on racial issues. A quote from the rioting, "Ain't no ambulances for no nigguhs tonight", was used as a title for a polemical speech that advocated black nationalist ideas, released as a recording in 1969;[5] it was also used for a 1972 collection of his poems.

Crouch was then active as a jazz drummer. Together with David Murray, he formed the group Black Music Infinity. In 1975, he sought to further his endeavors with a move from California to New York City, where he shared a loft with Murray above an East Village club called the Tin Palace. He was a drummer for Murray and with other musicians of the underground New York loft jazz scene. While working as a drummer, Crouch conducted the booking for an avant-garde jazz series at the club, as well as organizing occasional concert events at the Ladies' Fort. By his own admission he was not a good drummer, saying "The problem was that I couldn't really play. Since I was doing this avant-garde stuff, I didn't have to be all that good, but I was a real knucklehead."[6]

Crouch befriended Ralph Ellison and Albert Murray, who influenced his thinking in a direction less centered on race. He stated with regard to Murray's influence, "I saw how important it is to free yourself from ideology. When you look at things solely in terms of race or class, you miss what is really going on."[6] He made a final, public break with black nationalist ideology in 1979, in an exchange with Amiri Baraka in the Village Voice. He was also emerging as a public critic of recent cultural and artistic trends that he saw as empty, phony, or corrupt. His targets included the fusion and avant-garde movements in jazz (including his own participation in the latter) and literature that he saw as hiding their lack of merit behind racial posturing. As a writer for the Voice from 1980 to 1988, he was known for his blunt criticisms of his targets and tendency to excoriate their participants. It was during this period that he became a friend and intellectual mentor to Wynton Marsalis, and an advocate of the neotraditionalist movement that he saw as reviving the core values of jazz.[6] In 1987, he became an artistic consultant for the Jazz at Lincoln Center program, joined by Marsalis, who later became artistic director, in 1991.

After his stint at the Voice, Crouch published Notes of a Hanging Judge: Essays and Reviews, 1979–1989, which was selected by The Encyclopædia Britannica Yearbook as the best book of essays published in 1990.[7] That was followed by receipt of a Whiting Award in 1991, and a MacArthur Foundation "genius" grant and the Jean Stein Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1993.

Crouch continued to be an active author, producing works of fiction and nonfiction, articles for periodicals and newspaper columns. He was a columnist for the New York Daily News and a syndicated columnist. He also participated as a source in documentaries and as a guest in televised discussions. During the 2000s he was a featured commentator on Ken Burns' Jazz (2001) and Unforgivable Blackness (2005), on the life of the boxer Jack Johnson. He also published the novel Don't The Moon Look Lonesome? (2000), a collection of his reviews and writings on jazz, Considering Genius (2007), and a biography of the jazz musician Charlie Parker, Kansas City Lightning (2013). His posthumous collection Victory Is Assured (2022) was edited by Glenn Mott.

Crouch became less of a public figure due to declining health during his last decade. He died on September 16, 2020, at Calvary Hospital in New York City.[8] The cause of death was a "long, unspecified illness," though he also struggled with a bout of COVID-19 in the spring.[9] He was 74.

Crouch's personal and professional papers are held by the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library.[10]

Personal life

[edit]Crouch lived in Carroll Gardens, Brooklyn.[11]

Opinions

[edit]As a political thinker, Crouch was initially drawn to, then became disillusioned with, the Black Power movement of the late 1960s. His critiques of his former co-thinkers, whom he refers to as a "lost generation", are collected in Notes of a Hanging Judge: Essays and Reviews, 1979–1989 and The All-American Skin Game, or, The Decoy of Race: The Long and the Short of It, 1990–1994. He identified the embrace of racial essentialism among African-American[nb 1] leaders and intellectuals as a diversion from issues more central to the betterment of African Americans and society as a whole. In the 1990s, he upset many political thinkers when he declared himself a "radical pragmatist".[13] He explained, "I affirm whatever I think has the best chance of working, of being both inspirational and unsentimental, of reasoning across the categories of false division and beyond the decoy of race".[14]

In his syndicated column for the New York Daily News, Crouch frequently criticized prominent African Americans.[nb 1] Crouch was critical of, among others: Alex Haley, the author of The Autobiography of Malcolm X and Roots: The Saga of an American Family;[15] community leader Al Sharpton;[16] filmmaker Spike Lee;[17] scholar Cornel West,[18] and poet and playwright Amiri Baraka.[19]

Crouch was also a fierce critic of gangsta rap music, asserting that it promotes violence, criminal lifestyles, and degrading attitudes toward women.[20] With this viewpoint, he defended Bill Cosby's "Pound Cake Speech"[21] and praised a women's group at Spelman College for speaking out against rap music.[22][6] With regard to rapper Tupac Shakur he wrote, "what dredged-up scum you are willing to pay for is what scum you get, on or off stage."[23]

From the late 1970s, Crouch was critical of forms of jazz that diverge from what he regarded as its essential core values, similar to the opinions of Albert Murray on the same topic. In jazz critic Alex Henderson's assessment, Crouch was a "rigid jazz purist" and "a blistering critic of avant-garde jazz and fusion".[24] Crouch commented: "We should laugh at those who make artistic claims for fusion."[25]

In The New Yorker Robert Boynton wrote: "Enthusiastic, combative, and never averse to attention, Crouch has a virtually insatiable appetite for controversy."[6] Boynton also observed: "Few cultural critics have a vision as eclectic and intriguing as Stanley Crouch's. Fewer still actually fight to prove their points."[6] Crouch was fired from JazzTimes following his controversial article "Putting the White Man in Charge" in which he stated that, since the 1960s, "white musicians who can play are too frequently elevated far beyond their abilities in order to allow white writers to make themselves feel more comfortable about being in the role of evaluating an art from which they feel substantially alienated."[26]

Association with Wynton Marsalis and Ken Burns

[edit]Trumpeter Wynton Marsalis called Crouch "my best friend in the world" and "mentor".[27] The two met after Marsalis, at the age of 17, settled in New York City to attend the Juilliard School.[27] The two shared a close relationship,[27] Crouch having written liner notes for Marsalis' albums since his debut album in 1982.[28]

When Marsalis served as "Senior Creative Consultant" for Ken Burns' 2001 documentary Jazz, Crouch served on the film's advisory board and appears extensively.[29] Some jazz critics and aficionados cited the participation of Marsalis and Crouch specifically as reasons for what they believed to be the film's undue focus on traditional and straight-ahead jazz.[30]

After Jazz, Crouch appeared in other Burns films, including the DVD for the 2002 remastered version of The Civil War and the 2004 documentary Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson.[31]

Awards, honors, distinctions

[edit]- In 2004, Crouch was invited to a panel of judges for the PEN/Newman's Own Award, a $25,000 award designed to protect speech as it applies to the written word.[32]

- In 2005, he was selected as one of the inaugural fellows by the Fletcher Foundation, which awards annual fellowships to people working on issues of race and civil rights and directed by Professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr. of Harvard University.[33]

- In 2005, Crouch was named Man Of The Year by Patrick Lynch of the Police Benevolent Association of the City of New York for being "as bold in his support for New York City police officers as he is in his condemnation of the city’s “cheapskate” attitude in compensating the men and women who risk their lives every day to keep New York City safe and civil", which awards annual awards to men who perform acts of political allyship towards policing as a construct and has been presided over by Patrick J. Lynch since 1999.[34]

- Crouch served as president of the Louis Armstrong Educational Foundation from 2009 on.

- In 2016, Crouch was awarded the Windham–Campbell Literature Prize (nonfiction).[35]

- Crouch was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.[7]

Bibliography

[edit]Non-fiction

[edit]| Victory Is Assured: Uncollected Writings |

| Considering Genius: Writings on Jazz |

| Kansas City Lightning: The Rise and Times of Charlie Parker |

| The Artificial White Man: Essays on Authenticity |

| Always in Pursuit: Fresh American Perspectives, 1995-1997 |

| The All-American Skin Game, or, The Decoy of Race: The Long and the Short of It, 1990–1994 |

| Notes of a Hanging Judge: Essays and Reviews, 1979–1989 |

| Reconsidering the Souls of Black Folk, with Playthell G. Benjamin |

| One Shot Harris: The Photographs of Charles "Teenie" Harris |

Fiction

[edit]| Don't the Moon Look Lonesome? (2000) |

Poetry

[edit]| Ain't No Ambulances for No Nigguhs Tonight (1972) |

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Roberts, Sam (September 16, 2020). "Stanley Crouch, Critic Who Saw American Democracy in Jazz, Dies at 74". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ Garner, Dwight (October 10, 2013). "Stanley Crouch's 'Kansas City Lightning,' on Charlie Parker". The New York Times.

- ^ "Stanley Crouch". NNDB. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- ^ "California Birth Index (1905-1995)". SFGenealogy. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- ^ "HIP WAX (hipwax.com) VINYL RECORDS -- Funk, Soul, Funky Rock, Disco, Breakbeats". www.hipwax.com.

- ^ a b c d e f Boynton, Robert S. (November 6, 1995). "The Professor of Connection: A profile of Stanley Crouch". The New Yorker. pp. 97–116. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ^ a b "Louis Armstrong Educational Foundation". Louisarmstrongfoundation.org. Retrieved July 26, 2021.

- ^ Iverson, Ethan (September 16, 2020), "Stanley Crouch, Towering Jazz Critic, Dead At 74", National Public Radio (NPR).

- ^ West, Michael J. (September 17, 2020). "Stanley Crouch 1945–2020". JazzTimes.

- ^ "The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture Remembers Stanley Crouch". NYPL.org. September 22, 2020.

- ^ Crouch, Stanley (March 28, 2011). "This crazy quilt called America", New York Daily News. Retrieved February 21, 2019: "In my Brooklyn neighborhood of Carroll Gardens, I often ride my bike over to the Clover Club to hear the Michael Arenella Quartet."

- ^ Crouch, Stanley (January 10, 2010). "Then & now, I'm a Negro: The people who used that word gave it majesty". NY Daily News.

- ^ Author unidentified (January 30, 1995). "The 100 Smartest New Yorkers". New York Magazine, vol. 28, no. 5, p. 41.

- ^ Crouch, Stanley (1995), The All-American Skin Game; or, The Decoy of Race, Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0-679-44202-8.

- ^ Crouch, Stanley (April 12, 1998). "The Roots of Alex Haley's Fraud". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on July 10, 2012. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ^ Lamb, Brian (May 12, 1996). "The All-American Skin Game, or the Decoy of Race". Booknotes. C-SPAN. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ^ Crouch, Stanley (April 25, 2011). "Nation in love with minstrelsy: Spike Lee, Tyler Perry, Snoop Dogg and struggle to define blackness". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on May 15, 2012. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ^ Crouch, Stanley (May 23, 2011). "Cornel West is an expert showman but nothing more: The lead huckster of the Ivy League's takedown". New York Daily News. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ^ Watts, Jerry Gafio (2001). Amiri Baraka: The Politics and Art of a Black Intellectual. New York: New York University Press. p. 203. ISBN 0-8147-9373-8.

- ^ Crouch, Stanley (March 12, 1997). "Fatal Attraction: Rappers & Violence". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on May 15, 2012. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ^ Crouch, Stanley (May 27, 2004). "Some Blacks Stand Tall Against the Buffoonery". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on July 1, 2012. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ^ Crouch, Stanley (April 23, 2004). "Hip Hop Takes a Hit; Black Women Are Starting to Fight Rap's Degrading Images". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on May 15, 2012. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ^ Crouch, Stanley (September 11, 1996). "Tupac shows risk of being rapped up in stage life". New York Daily News. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ^ Henderson, Alex. "Stanley Crouch - Biography". allmusic. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ^ Crouch, Stanley (March 2002). "Four-Letter Words: Rap & Fusion". JazzTimes. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ^ Crouch, Stanley (April 2003). "Putting the White Man in Charge". JazzTimes. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Wynton Marsalis - Pulitzer Prize for Music". The Achiever Gallery. American Academy of Achievement. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ^ "Wynton Marsalis - Credits". allmusic.com. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ^ "Jazz". PBS.org. Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved September 4, 2007.

- ^ Stevens, Jan (2001). "On Ken Burns JAZZ documentary - and Bill Evans". The Bill Evans Webpages. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ^ "Stanley Crouch". Internet Movie Database. imdb.com. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ^ "PEN/Newman's Own First Amendment Award". PEN American Center. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ^ Bernstein, Elizabeth (April 15, 2005). "Giving Back" (PDF). The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ^ "PBA names Stanley Crouch 'Man of the Year'" (Press release). September 2, 2005. Retrieved July 18, 2021.

- ^ "Stanley Crouch". Windham–Campbell Literature Prize. February 29, 2016. Retrieved March 2, 2016.

External links

[edit]- 1945 births

- 2020 deaths

- 20th-century African-American writers

- 20th-century American essayists

- 20th-century American male writers

- 20th-century American novelists

- 21st-century African-American writers

- 21st-century American male writers

- 21st-century American non-fiction writers

- 21st-century American novelists

- African-American novelists

- American columnists

- American male non-fiction writers

- American male novelists

- American music critics

- American music journalists

- Harper's Magazine people

- Jazz writers

- MacArthur Fellows

- Novelists from New York (state)

- People from Carroll Gardens, Brooklyn

- Pomona College faculty

- Radical centrist writers

- Writers from Brooklyn

- Writers from Los Angeles