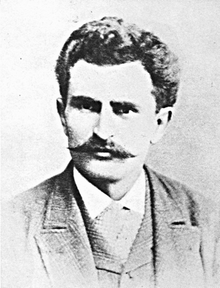

Errico Malatesta

Errico Malatesta | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 4 December 1853 |

| Died | 22 July 1932 (aged 78) |

| Occupation(s) | Revolutionary, activist, writer |

Philosophy career | |

| School | Anarcho-communism |

| Signature | |

Errico Malatesta (4 December 1853 – 22 July 1932) was an Italian anarchist propagandist and revolutionary socialist. He edited several radical newspapers and spent much of his life exiled and imprisoned, having been jailed and expelled from Italy, Britain, France, and Switzerland. Originally a supporter of insurrectionary propaganda by deed, Malatesta later advocated for syndicalism. His exiles included five years in Europe and 12 years in Argentina. Malatesta participated in actions including an 1895 Spanish revolt and a Belgian general strike. He toured the United States, giving lectures and founding the influential anarchist journal La Questione Sociale. After World War I, he returned to Italy where his Umanità Nova had some popularity before its closure under the rise of Mussolini.

Biography

[edit]Early years

[edit]Errico Malatesta was born on 4 December 1853[1][2] to a family of middle-class landowners in Santa Maria Maggiore, at the time part of the city of Capua (currently an autonomous municipality renamed Santa Maria Capua Vetere, in the province of Caserta), at the time part of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. More distantly, his ancestors ruled Rimini as the House of Malatesta. The first of a long series of arrests came at age fourteen, when he was apprehended for writing an "insolent and threatening" letter to King Victor Emmanuel II.[3][4]

In April 1877, Malatesta, Carlo Cafiero, Sergey Stepnyak-Kravchinsky and about thirty others started an insurrection in the province of Benevento, taking the villages of Letino and Gallo without a struggle. The revolutionaries burnt tax registers and declared the end of the King's reign and were met with enthusiasm. After leaving Gallo, however, they were arrested by government troops and held for sixteen months before being acquitted. After Giovanni Passannante's murder attempt on the king Umberto I, the radicals were kept under constant surveillance by the police. Even though the anarchists claimed to have no connection to Passannante, Malatesta, being an advocate of social revolution, was included in this surveillance. After returning to Naples, he was forced to leave Italy altogether in the fall of 1878 because of the intense surveillance, beginning his life in exile.[5]

Years of exile

[edit]

He went to Egypt briefly, visiting some Italian friends but was soon expelled by the Italian Consul.[5] After working his passage on a French ship and being refused entry to Syria, Turkey and Italy, he landed in Marseille where he made his way to Geneva, Switzerland – then something of an anarchist centre.[5] It was there that he befriended Élisée Reclus and Peter Kropotkin, helping the latter to produce La Révolte. The Swiss respite was brief, however, and after a few months he was expelled from Switzerland, travelling first to Romania before reaching Paris, where he worked briefly as a mechanic.[6]

In 1881, he set out for a new home in London. He would come and go from that city for the next 40 years.[6] There, Malatesta worked as a mechanic.[7] Emilia Tronzio, Malatesta's mistress in the 1870s, was the step-sister of the internationalist Tito Zanardelli.[8] With Malatesta's consent and support she married Giovanni Defendi, who came to stay with Malatesta in London in 1881 after being released from jail.[9]

Malatesta attended the July 1881 Anarchist Congress in London. Other delegates included Peter Kropotkin, Francesco Saverio Merlino, Marie Le Compte, Louise Michel and Émile Gautier. While respecting "complete autonomy of local groups" the congress defined propaganda actions that all could follow and agreed that "propaganda by the deed" was the path to social revolution.[10]

With the outbreak of the Anglo-Egyptian War in 1882, Malatesta organised a small group to help fight against the British. In August, he and three other men departed for Egypt. They landed in Abu Qir, then travelled towards Ramleh, Alexandria. After a difficult crossing of Lake Mariout, they were surrounded and detained by British forces, without having undertaken any fighting. He secretly returned to Italy the following year.[11]

In Florence he founded the weekly anarchist paper La Questione Sociale (The Social Question) in which his most popular pamphlet, Fra contadini (Among Farmers), first appeared. Malatesta went back to Naples in 1884—while waiting to serve a three-year prison term—to nurse the victims of a cholera epidemic. Once again, he fled Italy to escape imprisonment, this time heading for South America. He lived in Buenos Aires from 1885 until 1889, resuming publication of La Questione Sociale and spreading anarchist ideas among the Italian émigré community there.[6] He was involved in the founding of the first militant workers' union in Argentina and left an anarchist impression in the workers' movements there for years to come.[6]

Returning to Europe in 1889, Malatesta first published a newspaper called L'Associazione in Nice, remaining there until he was once again forced to flee to London.

Arrest in Italy

[edit]

The late 1890s were a time of social turmoil in Italy, marked by bad harvests, rising prices, and peasant revolts.[6] Strikes of workers were met by demands for repression and for a time it seemed as though government authority was hanging by a thread.[6] Malatesta found the situation irresistible and early in 1898 he returned to the port city of Ancona to take part in the blossoming anarchist movement among the dockworkers there.[6] Malatesta was soon identified as a leader during street fighting with police and arrested; he was therefore unable to participate further in the dramatic industrial and political actions of 1898 and 1899.[6]

From jail, Malatesta took a hard line against participation in elections on behalf of liberal and socialist politicians, contradicting Saverio Merlino and other anarchist leaders who argued in favor of electoral participation as an emergency measure during times of social turmoil.[6] Malatesta was convicted of "seditious association" and sentenced to a term of imprisonment on the island of Lampedusa.[12]

Escape and later life

[edit]He was able to escape from prison in May 1899, however, and he made his way home to London via Malta and Gibraltar.[13] His escape occurred with the help of comrades around the world, including anarchists in Paterson, New Jersey, London and Tunis, who helped arrange for him to leave the island on a ship of Greek sponge fishermen, who took him to Sousse.[14]

In subsequent years, Malatesta visited the United States, speaking there to anarchists in the Italian and Spanish immigrant communities.[13] Home again in London, he was closely watched by the police, who increasingly regarded anarchists as a threat following the July 1900 assassination of Umberto I by an Italian anarchist who had been living in Paterson, New Jersey.[13]

In 1902, the founding congress of the Unión Obrera Democrática Filipina - first national trade union federation in the Philippines - adopted Malatesta's book Between Peasants as being part of the political foundation of the movement.[15]

Return to London

[edit]By 1910, he had opened an electrical workshop in London at 15 Duncan Terrace Islington and allowed the jewel thief George Gardenstein to use his premises. On 15 January 1910, he sold oxyacetylene cutting equipment for £5 (£500 at 2013 monetary values) to George Gardenstein so that he could break into the safe at H. S. Harris jewellers Houndsditch. Gardenstein led the gang that mounted the abortive Houndsditch robbery that is the precursor to the Siege of Sidney Street. Malatesta's cutting gear is on permanent display at the City of London Police museum at Wood Street police station.[16]

While based in London, Malatesta made clandestine trips to France, Switzerland and Italy and went on a lecture tour of Spain with Fernando Tarrida del Mármol. During this time, he wrote several important pamphlets, including L'Anarchia.[17] Malatesta then took part in the International Anarchist Congress of Amsterdam (1907), where he debated in particular with Pierre Monatte on the relation between anarchism and syndicalism or trade unionism. The latter thought that syndicalism was revolutionary and would create the conditions of a social revolution, while Malatesta considered that syndicalism by itself was not sufficient.[18]

After the First World War, Malatesta eventually returned to Italy for the final time. Two years after his return, in 1921, the Italian government imprisoned him, again, although he was released two months before the fascists came to power. From 1924 until 1926, when Benito Mussolini silenced all independent press, Malatesta published the journal Pensiero e Volontà, although he was harassed and the journal suffered from government censorship. He was to spend his remaining years leading a relatively quiet life, earning a living as an electrician. After years of suffering from a weak respiratory system and regular bronchial attacks, he developed bronchial pneumonia from which he died after a few weeks, despite being given 1,500 litres of oxygen in his last five hours. He died on Friday 22 July 1932. He was an atheist.[19]

Political beliefs

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Anarchism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Anarchist communism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Communism in Italy |

|---|

|

|

|

David Goodway writes that Malatesta held a "Mazzini-like role" and was "the leader of the Italian anarchist movement during its most important years. While other leaders of the International changed their opinions or abandoned politics, Malatesta remained firm in his original convictions for a half-century". In this sense, only Malatesta "remained devoted to anarchism by the end of the 1870s". Goodway argues that Malatesta was able to do so "by modifying his optimistic approach, substituting one of the more sophisticated versions of anarchism". Goodway writes that Malatesta developed "a two-pronged strategy" by the 1880s and early 1900s. Malatesta sought on one hand "to unify the anarchist and anti-parliamentary socialists into a new anarchist socialist party" as "anarchism was a minority movement within the Italian left", hence "Malatesta and his followers hoped to galvanize the elements of regional socialist group (the Fasci Siciliani, the Revolutionary Socialist Party of Romagna, and the Partito Operaio) into a new anti-parliamentary socialist party". On the other hand, Malatesta was "one of the first anarchists to stress a syndicalist strategy" and anarchists "had to prod the socialists into insurrections and remain a revolutionary conscience afterwards during socialist reconstruction". Goodway further writes that "Malatesta defined this type of anarchist communism as 'anarchism without adjectives'", described by Goodway as "a concept which he had developed with a group of Spanish anarchist intellectuals in the process mediating between mutually hostile collectivists and communists". In stressing "tolerance within the libertarian movement", Malatesta hoped that "Marxist socialists would permit the anarchists liberty for their own movement in post-revolutionary society".[20]

According to Davide Turcato, the label "anarchist socialism" came to characterize Malatesta's brand of anarchism as he "proclaimed the socialist character of anarchism and urged anarchists to regain contact with the working masses, especially through involvement in the labor movement". For Malatesta, "demanding the anarchists' admission to the congress meant reasserting socialism and labor movement as central to anarchism; conversely, the Marxists' effort to exclude anarchists aimed at denying that they had a place among socialist and workers". According to Turcato, "Malatesta's struggle for admission to the congress was a statement of his new tactics". Turcato writes how "Malatesta recalled in the Labour Leader that in the old International both Marxists and Bakuninists wished to make their program triumph. In the struggle between centralism and federalism, class struggle and economic solidarity got neglected, and the International perished in the process. In contrast, anarchists were not presently demanding anyone to renounce their program. They only asked for divisions to be left out of the economic struggle, where they had no reason to exists ('Should')". In other words, "the issue was no longer hegemony, but the contrast between an exclusive view of socialism, for which one political idea was to be hegemonic, and an inclusive one, for which multiple political views were to coexist, united in the economic struggle. [...] The matter of the question had changed: the controversy was no longer with the anarchists, but about the anarchists".[21]

Anarchists who influenced Malatesta's political beliefs included Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Mikhail Bakunin, Carlo Cafiero,[22] Peter Kropotkin and Élisée Reclus. In turn, Malatesta's works influenced Marxist philosopher Antonio Gramsci and anarcha-feminist activist Virginia Bolten,[23] as well as the Argentine Regional Workers' Federation[24] and wider Argentine anarchist movement.[25]

On labour unions

[edit]Malatesta argued with Pierre Monatte at the Amsterdam Conference of 1907 against pure syndicalism. Malatesta thought that trade unions were reformist and could even be at times conservative. Along with Christiaan Cornelissen, he cited as example labor unions in the United States, where trade unions composed of skilled qualified workers sometimes opposed themselves to un-skilled workers in order to defend their relatively privileged position.[18] Malatesta warned that the syndicalists aims were in perpetuating syndicalism itself whereas anarchists must always have overthrowing capitalism and the state, the anarchist ideal of communist society as their end and consequently refrain from committing to any particular method of achieving it.[26]

Malatesta's arguments against the doctrine of revolutionary unions known as anarcho-syndicalism were later developed in a series of articles, where he wrote that "I am against syndicalism, both as a doctrine and a practice, because it strikes me as a hybrid creature."[27] Despite their drawbacks, he advocated activity in the trade unions, both because they were necessary for the organization and self-defense of workers under a capitalist state regime, and as a way of reaching broader masses. Anarchists should have discussion groups in unions, as in factories, barracks and schools, but "anarchists should not want the unions to be anarchist."[28]

Malatesta thought that "[s]yndicalism [...] is by nature reformist" like all unions.[29] While anarchists should be active in the rank and file, he said "any anarchist who has agreed to become a permanent and salaried official of a trade union is lost to anarchism."[30] While some anarchists wanted to split from conservative unions to form revolutionary syndicalist unions, Malatesta predicted they would either remain an "affinity group" with no influence, or go through the same process of bureaucratization as the unions they left.[31] This early statement of what would come to be known as "the rank-and-file strategy" remained a minority position within anarchism, but Malatesta's ideas did have echoes in the anarchists Jean Grave and Vittorio Aurelio.

Selected works

[edit]- Between Peasants: A Dialogue on Anarchy (1884)

- Anarchy (1891)

- At the Cafe: Conversations on Anarchism (1922)

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Gibbard, Paul (2005). "Malatesta, Errico". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/58609. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Lotha, Gloria; Promeet, Dutta (18 July 2020). "Errico Malatesta". Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Archived from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ^ Guérin, Daniel (2005). No Gods, No Masters. Vol. 1–4. AK Press. p. 349. ISBN 9781904859253. Archived from the original on 11 January 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ^ Benewick, Robert (1998). "Errico Malatesta 1853–1932". The Routledge Dictionary of Twentieth-Century Political Thinkers. Psychology Press. p. 202. ISBN 9780415096232. Archived from the original on 11 January 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ^ a b c Joll, James (1964). The Anarchists. Boston, MA: Little, Brown & Co. p. 174.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Joll, James (1964). The Anarchists. Boston, MA: Little, Brown & Co. p. 175.

- ^ Paola, Pietro Di (2013). The Knights Errant of Anarchy: London and the Italian Anarchist Diaspora (1880-1917). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9781846319693. Archived from the original on 23 January 2022. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- ^ Dipaola, Pietro (April 2004). "The 1880s and the International Revolutionary Socialist Congress". Italian Anarchists in London (PDF). p. 54. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- ^ "Sur les traces de Malatesta" [In the footsteps of Malatesta]. A Contretemps (in French). January 2010. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- ^ Bantman, Constance (2006). "Internationalism without an International? Cross-Channel Anarchist Networks, 1880–1914". Revue belge de philologie et d'histoire. 84 (84–4): 965. doi:10.3406/rbph.2006.5056. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ^ Fabbri, Luigi (1936). "Life of Malatesta". Anarchy Archives. Archived from the original on 29 December 2016. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- ^ Joll, James (1964). The Anarchists. Boston, MA: Little, Brown & Co. pp. 175–176.

- ^ a b c Joll, James (1964). The Anarchists. Boston, MA: Little, Brown & Co. p. 176.

- ^ Carminati, Lucia (2017). "Alexandria, 1898: Nodes, Networks, and Scales in Nineteenth-Century Egypt and the Mediterranean". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 59: 127–153. doi:10.1017/S0010417516000554. S2CID 151859073.

- ^ Guevarra, Dante G. History of the Philippine Labor Movement. Sta. Mesa, Manila: Institute of Labor & Industrial Relations, Polytechnic University of the Philippines, 1991. pp. 17–18

- ^ City of London Police museum.

- ^ Malatesta, Errico (1974) [1891]. Malatesta's Anarchy. Translated by Richards, Vernon. London: Freedom Press. ISBN 9780904491111. Archived from the original on 23 September 2012. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- ^ a b "Extract of Malatesta's declaration" (in French). Archived from the original on 28 September 2007.

- ^ Toda, Misato (1988). Errico Malatesta da Mazzini a Bakunin [Errico Malatesta from Mazzini to Bakunin] (in Italian). Guida Editori. p. 75.

- ^ Goodway, David (26 June 2013). For Anarchism (RLE Anarchy). Milton: Routledge. p. 39. ISBN 9781135037567.

- ^ Turcato, Domenico (2012). Making Sense of Anarchism: Errico Malatesta's Experiments with Revolution, 1889–1900 (illustrated ed.). New York: Springer. p. 137. ISBN 9781137271402.

- ^ Pernicone, Nunzio (1993). Italian Anarchism, 1864–1892. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-05692-7. LCCN 92-46661.

- ^ Molyneux, Maxine (2001). "'No God, No Boss, No Husband!' Anarchist Feminism in Nineteenth-Century Argentina". Women's Movements in International Perspective: Latin America and Beyond. Palgrave MacMillan. pp. 13–37. doi:10.1057/9780230286382_2. ISBN 978-0-333-78677-2. LCCN 00-062707.

- ^ Oved, Yaacov (1997). "The Uniqueness of Anarchism in Argentina". Estudios Interdisciplinarios de America Latina y el Caribe. 8 (1): 63–76. ISSN 0792-7061.

- ^ Colombo, Eduardo (1971), "Anarchism in Argentina and Uruguay", in Apter, David E.; Joll, James (eds.), Anarchism Today, Garden City, New York: Anchor Books, pp. 211–244

- ^ Skirda, Alexandre (2002). Facing the enemy: a history of anarchist organization from Proudhon to May 1968. A. K. Press. p. 89. ISBN 1-902593-19-7.

- ^ Malatesta, Errico (March 1926). "Further Thoughts on Anarchism and the Labour Movement". Archived from the original on 30 January 2012. Retrieved 8 February 2012.

- ^ Malatesta, Errico (April–May 1925). "Syndicalism and Anarchism". Archived from the original on 30 January 2012. Retrieved 8 February 2012.

- ^ Malatesta, Errico (December 1925). "The Labor Movement and Anarchism". Archived from the original on 30 January 2012. Retrieved 8 February 2012.

- ^ Quoted in Anarchism: From theory to practice Archived 24 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine Daniel Guerin, Monthly Review Press, 1970

- ^ Malatesta, Errico (December 1925). "The Labor Movement and Anarchism". El Productor. Archived from the original on 30 January 2012. Retrieved 8 February 2012.

Further reading

[edit]- Bonanno, Alfredo M. (2011). Errico Malatesta and Revolutionary Violence (PDF). Translated by Weir, Jean. London: Elephant Editions. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 November 2020.

- Luigi Fabbri, Life of Malatesta, Adam Wight, trans. (1936)

- Vernon Richards (ed.), Errico Malatesta – His Life And Ideas. Freedom Press, 1965.

- Enrico Tuccinardi – Salvatore Mazzariello, Architettura di una chimera. Rivoluzione e complotti in una lettera dell'anarchico Malatesta reinterpretata alla luce di inediti documenti d'archivio, Mantova, Universitas Studiorum, 2014. ISBN 978-88-97683-7-28

- Davide Turcato (Editor) – The Complete Works of Malatesta, Vol. III: A Long and Patient Work: The Anarchist Socialism of L’Agitazione, 1897–1898, AK Press, 2017. ISBN 9781849351478

External links

[edit]- Libcom.org Malatesta Archive

- Articles by and about Malatesta

- Errico Malatesta Page at the Anarchist Encyclopedia

- Malatesta articles at the Kate Sharpley Library

- Works by Errico Malatesta at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Errico Malatesta at the Internet Archive

- Works by Errico Malatesta in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works by Errico Malatesta at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Errico Malatesta at RevoltLib

- The Radical Pamphlet Collection at the Library of Congress has materials written by Errico Malatesta.

Films

[edit]- Malatesta (1970), directed by Peter Lilienthal; see also Malatesta at IMDb

- San Michele aveva un gallo at IMDb , 1972 film loosely based on Malatesta's life

- 1853 births

- 1932 deaths

- Anarchist theorists

- Anarchists without adjectives

- Anarcho-communists

- Italian anti-capitalists

- Italian anarchists

- Italian atheists

- Italian anti-fascists

- Italian communists

- Italian socialists

- Members of the International Workingmen's Association

- People from Santa Maria Capua Vetere

- Burials at Campo Verano