Temple Entry Proclamation

| This article is part of a series on |

| Reformation in Kerala |

|---|

|

| Background |

| Notable people |

|

| Others |

The Temple Entry Proclamation was issued by Maharaja Chithira Thirunal Balarama Varma on November 12, 1936. The Proclamation abolished the ban on the backward and marginalised communities, from entering Hindu temples in the Princely State of Travancore, now part of Kerala, India.[1]

The proclamation was a milestone in the history of Travancore and Kerala. Temple Entry Proclamation Day is considered to be a social reformation day by the Government of Kerala.[2]

History

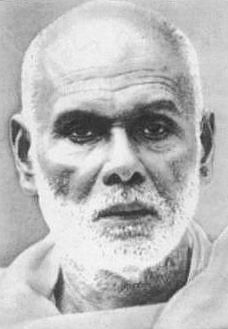

[edit]Following the campaign to introduce social reform in Travancore inspired by the teachings of Narayana Guru and others, a deputation of six leaders appointed by the Harijan Sevak Sangh toured the princely state to obtain support from caste Hindus for the backward castes to be allowed to enter state-operated temples.[citation needed]

Vaikom Satyagraha

[edit]According to historian Romila Thapar, protests in 1924–25 against the prohibition of Dalits using a public road near a temple in Vaikom were a significant precursor to the temple entry movement. Known as the Vaikom Satyagraha, it involved the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi. The protests sought equal rights of access in areas previously restricted to members of forward castes. The protests expanded to become a movement seeking rights of access to the interior of the temples themselves. These peaceful protests inspired the future, it widely criticized that Temple Entry Declaration was done in order to prevent backward caste people from converting in mass to Christianity. The then-Travancore rulers feared that if the Hindu majority is lost in the country, it will be difficult for them to manage.[3]

Temple entry committee

[edit]

In 1932, the Maharajah, Chithira Thirunal appointed a committee to examine the question of temple entry.[citation needed] This opened the possibility of reversing the opposition to the practice that had been shown by his predecessors, Moolam Thirunal and Regent Maharani Sethu Lakshmi Bayi. Subsequent to a meeting with Gandhi, Bayi had released those who had been imprisoned by Moolam Thirunal for involvement with the Vaikom Satyagraha and had opened the north, south and west public roads that provided access to Vaikom Mahadeva Temple to all castes. She refused to open the eastern road to the temple because it was used by Brahmins. She avoided acting on Gandhi's advice by pointing out that she was a regent for her minor nephew, Chithira Thirunal and so had no power to do so.

Annoyed with this response Gandhi asked the 12-year-old prince, who immediately promised that it would happen during his reign.[4] This incident was later quoted by K. R. Narayanan, the former President of India, in his speech referring to the progressive mind of Chithira Thirunal.

During the Vaikom Sathyagraha, Mahatma Gandhi visited Kerala. At that time, Sree Chithira Thirunal was a young man, and had not ascended the throne. Gandhiji asked: "When you attain majority and assume full authority, will you allow Harijans to enter the temple?". The twelve-year-old Maharajah said without hesitation, "Certainly". This was not the result of anybody's advice. He spoke his own mind. It came from his own thinking and that is why I say, in spite of all the advice and influences in which he was enveloped, he had a mind and he had a policy of his own.[5]

The Regent's refusal to act on temple entry rights attracted criticism from people such as Mannathu Padmanabhan, who accused her of being under the influence of the Brahmins and said that her excuse that she had no power to decide was a lie.[6][page needed]

Royal proclamation and its aftermath

[edit]

Chithira Thirunal signed the Proclamation on the eve of his 24th birthday in 1936. C. P. Ramaswami Iyer said of the decision that:

The Proclamation is a unique occasion in the history of India and specially of Hinduism. It fell to the lot of His Highness, not as a result of agitation, although some people have claimed to result as due to agitation, but suo moto and of his own free will, to have made it possible for every Hindu subject to enter the historic temples of this land of faith and bend in adoration before the Supreme. Such an act required a minority vision and usage amidst difficulties and handicaps. when it is remembered that this decision was a purely voluntary act, on the part of sovereign, solicitous for the welfare of this subjects and was not the result of any immediate pressure, the greatness of the achievement becomes even more apparent. This action broke the calamity of Hindu religion and helped to strengthen the Hindus.[7]

In an open letter addressed to the maharajah, Gandhi said:

People call me "The Mahatma" and I don’t think I deserve it. But in my view, you have in reality become a "Mahatma"(great soul) by your proclamation at this young age, breaking the age-old custom and throwing open the doors of the Temples to our brothers and sisters whom the hateful tradition considered as untouchables. I verily believe that when all else is forgotten, this one act of the Maharajah- the Proclamation- will be remembered by future generation with gratitude and hope that all other Hindu Princes will follow the noble example set by this far-off ancient Hindu State.[8][9][10]

Historians[who?] believe that it was Iyer's legal skill that overcame the practical difficulties posed by the orthodox Hindus before the proclamation. He foresaw the objections that could be raised against temple entry and dealt with them one by one. He was also able to ensure that the actual declaration was known beforehand to few people.

The Universities of Andhra and Annamalai conferred D.Litt. degrees on the Maharajah, and life-size statues of him were erected in Trivandrum and Madras.[11]

Sociologists[who?] believe that the Proclamation struck at the root of caste discrimination in Travancore and that by serving to unite Hindus it prevented further conversions to other religions. The Proclamation was the first of its kind in a princely state as well as in British India. Even though there were agitations in various parts of India as well as rest of Kerala for temple entry, none managed to achieve their aim.

Temple entry in Cochin And Malabar

[edit]The Travancore Temple Entry Proclamation did not have a serious influence in Cochin or British Malabar as the Maharajah of Cochin and the Zamorin were staunch opponents of temple entry for dalits.[12][13] The Cochin ruler even forbade rituals like Arattu (holy bathing) and Para (holy procession) in Tripunithura and Chottanikkara temples. Eventually, a temple entry proclamation was issued in Cochin on December 22,1947 which came into force on April 14,1948. Even when universal temple entry was granted in 1947 the Cochin Maharajah made an exemption in the bill so as to keep his family temple, "Sree Poornathrayeesha", out of the purview of temple entry. The inhabitants of the Malabar region also finally received this right, as per the Madras Temple entry proclamation issued on June 12,1947.

The Zamorin of Malabar had no wish to change the existing customs and usages in temples; on hearing the news of the Travancore Temple Entry proclamation he said that the Travancore Maharajah did not have the authority to do so as he was only a trustee of the temples which were under the supervision of Hindu Religions Endowment Board. He also sent a memorandum to the authorities claiming no one had the authority to take decisions regarding temple entry as they were private properties. Universal temple entry was only granted in Malabar region in 1947 after India's independence.[14]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Religion and Social Conflict in South Asia By Bardwell L. Smith, p42, Google book

- ^ Religion and Social Conflict in South Asia By Bardwell L. Smith, p42, Google book

- ^ "Extreme injustice led to Vaikom Satyagraha, says Romila Thapar". The Hindu. 22 July 2009. Archived from the original on 28 November 2013. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- ^ Gandhi Smarak Nidhi, Gandhi Peace Foundation (New Delhi, India). Gandhi Marg. The University of California: Gandhi Peace Foundation, 2007. pp. 93–103.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ K. R. Narayanan, His Excellency. "'INCARNATION OF MODESTY'- First Sree Chithira Thirunal Memorial Speech delivered at Kanakakunnu Palace, Trivandrum on 25-10-1992". Archived from the original on 20 May 2012. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- ^ Keith E. Yandell Keith E. Yandell, John J. Paul. Religion and Public Culture: Encounters and Identities in Modern South India.

- ^ inflibnet.ac.in, shodhganga. "CHAPTER – VI TEMPLE ENTRY FREEDOM IN KERALA" (PDF). shodhganga. RESEARCHERS OF MAHATMA GANDHI UTY, KOTTAYAM, KERALA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 13 December 2014.

- ^ Of India, Supreme Court. "Good Governance: Judiciary and the rule of law" (PDF). Sree Chitira Thirunal Memorial Lecture, 29 December 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 October 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- ^ The letter was published in the Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi in the 98th volume.

- ^ "Setting the record right". The New Indian Express. 3 August 2013. Archived from the original on 3 March 2014. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- ^ Mahadevan, G. "Temple Entry Proclamation the greatest act of moral freedom: Uthradom Tirunal". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- ^ inflibnet.ac.in, shodhganga. "CHAPTER – VI TEMPLE ENTRY FREEDOM IN KERALA" (PDF). shodhganga. RESEARCHERS OF MAHATMA GANDHI UTY, KOTTAYAM, KERALA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 February 2014.

- ^ "The Casabianca of Travancore". The Hindu. 26 March 2002.

Incidentally it came as a surprise to many at the time that the then Maharaja of adjacent Cochin State who was later applauded by Nehru for being the first princely ruler in 1946 to constitute a responsible government was a staunch opponent of temple entry.

- ^ Digital Concepts Cochin, BeeHive Digital Concepts Cochin for; Mahatma Gandhi University Kottayam. "TEMPLE ENTRY FREEDOM IN KERALA" (PDF). Shodhganga.inflibnet.ac. CHAPTER VI: 1–46. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 14 February 2014.