Carbon sequestration

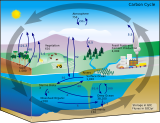

Carbon sequestration is the process of storing carbon in a carbon pool.[2]: 2248 It plays a crucial role in limiting climate change by reducing the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. There are two main types of carbon sequestration: biologic (also called biosequestration) and geologic.[3]

Biologic carbon sequestration is a naturally occurring process as part of the carbon cycle. Humans can enhance it through deliberate actions and use of technology. Carbon dioxide (CO

2) is naturally captured from the atmosphere through biological, chemical, and physical processes. These processes can be accelerated for example through changes in land use and agricultural practices, called carbon farming. Artificial processes have also been devised to produce similar effects. This approach is called carbon capture and storage. It involves using technology to capture and sequester (store) CO

2 that is produced from human activities underground or under the sea bed.

Plants, such as forests and kelp beds, absorb carbon dioxide from the air as they grow, and bind it into biomass. However, these biological stores may be temporary carbon sinks, as long-term sequestration cannot be guaranteed. Wildfires, disease, economic pressures, and changing political priorities may release the sequestered carbon back into the atmosphere.[4]

Carbon dioxide that has been removed from the atmosphere can also be stored in the Earth's crust by injecting it underground, or in the form of insoluble carbonate salts. The latter process is called mineral sequestration. These methods are considered non-volatile because they not only remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere but also sequester it indefinitely. This means the carbon is "locked away" for thousands to millions of years.

To enhance carbon sequestration processes in oceans the following chemical or physical technologies have been proposed: ocean fertilization, artificial upwelling, basalt storage, mineralization and deep-sea sediments, and adding bases to neutralize acids.[5] However, none have achieved large scale application so far. Large-scale seaweed farming on the other hand is a biological process and could sequester significant amounts of carbon.[6] The potential growth of seaweed for carbon farming would see the harvested seaweed transported to the deep ocean for long-term burial.[7] The IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate recommends "further research attention" on seaweed farming as a mitigation tactic.[8]

Terminology

[edit]| Part of a series on the |

| Carbon cycle |

|---|

|

The term carbon sequestration is used in different ways in the literature and media. The IPCC Sixth Assessment Report defines it as "The process of storing carbon in a carbon pool".[9]: 2248 Subsequently, a pool is defined as "a reservoir in the Earth system where elements, such as carbon and nitrogen, reside in various chemical forms for a period of time".[9]: 2244

The United States Geological Survey (USGS) defines carbon sequestration as follows: "Carbon sequestration is the process of capturing and storing atmospheric carbon dioxide."[3] Therefore, the difference between carbon sequestration and carbon capture and storage (CCS) is sometimes blurred in the media.[citation needed] The IPCC, however, defines CCS as "a process in which a relatively pure stream of carbon dioxide (CO2) from industrial sources is separated, treated and transported to a long-term storage location".[10]: 2221

Roles

[edit]In nature

[edit]Carbon sequestration is part of the natural carbon cycle by which carbon is exchanged among the biosphere, pedosphere (soil), geosphere, hydrosphere, and atmosphere of Earth.[citation needed] Carbon dioxide is naturally captured from the atmosphere through biological, chemical, or physical processes, and stored in long-term reservoirs.

Plants, such as forests and kelp beds, absorb carbon dioxide from the air as they grow, and bind it into biomass. However, these biological stores are considered volatile carbon sinks as long-term sequestration cannot be guaranteed. Events such as wildfires or disease, economic pressures, and changing political priorities can result in the sequestered carbon being released back into the atmosphere.[11]

In climate change mitigation and policies

[edit]Carbon sequestration - when acting as a carbon sink -[clarification needed] helps to mitigate climate change and thus reduce harmful effects of climate change. It helps to slow the atmospheric and marine accumulation of greenhouse gases, which is mainly carbon dioxide released by burning fossil fuels.[12]

Carbon sequestration, when applied for climate change mitigation, can either build on enhancing naturally occurring carbon sequestration or use technology for carbon sequestration processes.[needs copy edit]

Within the carbon capture and storage approaches, carbon sequestration refers to the storage component. Artificial carbon storage technologies can be applied, such as gaseous storage in deep geological formations (including saline formations and exhausted gas fields), and solid storage by reaction of CO2 with metal oxides to produce stable carbonates.[13]

For carbon to be sequestered artificially (i.e. not using the natural processes of the carbon cycle) it must first be captured, or it must be significantly delayed or prevented from being re-released into the atmosphere (by combustion, decay, etc.) from an existing carbon-rich material, by being incorporated into an enduring usage (such as in construction).[needs copy edit] Thereafter it can be passively stored or remain productively utilized over time in a variety of ways. For instance, upon harvesting, wood (as a carbon-rich material) can be incorporated into construction or a range of other durable products, thus sequestering its carbon over years or even centuries.[14] In industrial production, engineers typically capture carbon dioxide from emissions from power plants or factories.

For example in the United States, the Executive Order 13990 (officially titled "Protecting Public Health and the Environment and Restoring Science to Tackle the Climate Crisis") from 2021, includes several mentions of carbon sequestration via conservation and restoration of carbon sink ecosystems, such as wetlands and forests. The document emphasizes the importance of farmers, landowners, and coastal communities in carbon sequestration. It directs the Treasury Department to promote conservation of carbon sinks through market based mechanisms.[15]

Biological carbon sequestration on land

[edit]Biological carbon sequestration (also called biosequestration) is the capture and storage of the atmospheric greenhouse gas carbon dioxide by continual[contradictory]or enhanced biological processes. This form of carbon sequestration occurs through increased rates of photosynthesis via land-use practices such as reforestation and sustainable forest management.[16][17] Land-use changes that enhance natural carbon capture have the potential to capture and store large amounts of carbon dioxide each year. These include the conservation, management, and restoration of ecosystems such as forests, peatlands, wetlands, and grasslands, in addition to carbon sequestration methods in agriculture.[18] Methods and practices exist to enhance soil carbon sequestration in both agriculture and forestry.[19]

Forestry

[edit]

Forests are an important part of the global carbon cycle because trees and plants absorb carbon dioxide through photosynthesis. Therefore, they play an important role in climate change mitigation.[21]: 37 By removing the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide from the air, forests function as terrestrial carbon sinks, meaning they store large amounts of carbon in the form of biomass, encompassing roots, stems, branches, and leaves. Throughout their lifespan, trees continue to sequester carbon, storing atmospheric CO2 long-term.[22] Sustainable forest management, afforestation, reforestation are therefore important contributions to climate change mitigation.

An important consideration in such efforts is that forests can turn from sinks to carbon sources.[23][24][25] In 2019 forests took up a third less carbon than they did in the 1990s, due to higher temperatures, droughts and deforestation. The typical tropical forest may become a carbon source by the 2060s.[26]

Researchers have found that, in terms of environmental services, it is better to avoid deforestation than to allow for deforestation to subsequently reforest, as the former leads to irreversible effects in terms of biodiversity loss and soil degradation.[27] Furthermore, the probability that legacy carbon will be released from soil is higher in younger boreal forest.[28] Global greenhouse gas emissions caused by damage to tropical rainforests may have been substantially underestimated until around 2019.[29] Additionally, the effects of afforestation and reforestation will be farther in the future than keeping existing forests intact.[30] It takes much longer − several decades − for the benefits for global warming to manifest to the same carbon sequestration benefits from mature trees in tropical forests and hence from limiting deforestation.[31] Therefore, scientists consider "the protection and recovery of carbon-rich and long-lived ecosystems, especially natural forests" to be "the major climate solution".[32]

The planting of trees on marginal crop and pasture lands helps to incorporate carbon from atmospheric CO

2 into biomass.[33][34] For this carbon sequestration process to succeed the carbon must not return to the atmosphere from biomass burning or rotting when the trees die.[35] To this end, land allotted to the trees must not be converted to other uses. Alternatively, the wood from them must itself be sequestered, e.g., via biochar, bioenergy with carbon capture and storage, landfill or stored by use in construction.

Earth offers enough room to plant an additional 0.9 billion ha of tree canopy cover.[36] Planting and protecting these trees would sequester 205 billion tons of carbon.[36] To put this number into perspective, this is about 20 years of current global carbon emissions (as of 2019) .[37] This level of sequestration would represent about 25% of the atmosphere's carbon pool in 2019.[36]

Life expectancy of forests varies throughout the world, influenced by tree species, site conditions, and natural disturbance patterns. In some forests, carbon may be stored for centuries, while in other forests, carbon is released with frequent stand replacing fires. Forests that are harvested prior to stand replacing events allow for the retention of carbon in manufactured forest products such as lumber.[38] However, only a portion of the carbon removed from logged forests ends up as durable goods and buildings. The remainder ends up as sawmill by-products such as pulp, paper, and pallets.[39] If all new construction globally utilized 90% wood products, largely via adoption of mass timber in low rise construction, this could sequester 700 million net tons of carbon per year.[40][41] This is in addition to the elimination of carbon emissions from the displaced construction material such as steel or concrete, which are carbon-intense to produce.

A meta-analysis found that mixed species plantations would increase carbon storage alongside other benefits of diversifying planted forests.[9]

Although a bamboo forest stores less total carbon than a mature forest of trees, a bamboo plantation sequesters carbon at a much faster rate than a mature forest or a tree plantation. Therefore, the farming of bamboo timber may have significant carbon sequestration potential.[42]

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) reported that: "The total carbon stock in forests decreased from 668 gigatonnes in 1990 to 662 gigatonnes in 2020".[20]: 11 In Canada's boreal forests as much as 80% of the total carbon is stored in the soils as dead organic matter.[43][globalize]

The IPCC Sixth Assessment Report says: "Secondary forest regrowth and restoration of degraded forests and non-forest ecosystems can play a large role in carbon sequestration (high confidence) with high resilience to disturbances and additional benefits such as enhanced biodiversity."[44][45]

Impacts on temperature are affected by the location of the forest. For example, reforestation in boreal or subarctic regions has less impact on climate. This is because it substitutes a high-albedo, snow-dominated region with a lower-albedo forest canopy. By contrast, tropical reforestation projects lead to a positive change such as the formation of clouds. These clouds then reflect the sunlight, lowering temperatures.[46]: 1457

Planting trees in tropical climates with wet seasons has another advantage. In such a setting, trees grow more quickly (fixing more carbon) because they can grow year-round. Trees in tropical climates have, on average, larger, brighter, and more abundant leaves than non-tropical climates. A study of the girth of 70,000 trees across Africa has shown that tropical forests fix more carbon dioxide pollution than previously realized. The research suggested almost one-fifth of fossil fuel emissions are absorbed by forests across Africa, Amazonia and Asia. Simon Lewis stated, "Tropical forest trees are absorbing about 18% of the carbon dioxide added to the atmosphere each year from burning fossil fuels, substantially buffering the rate of change."[47][obsolete source]

Wetlands

[edit]

Wetland restoration involves restoring a wetland's natural biological, geological, and chemical functions through re-establishment or rehabilitation.[49] It is a good way to reduce climate change.[50] Wetland soil, particularly in coastal wetlands such as mangroves, sea grasses, and salt marshes,[50] is an important carbon reservoir; 20–30% of the world's soil carbon is found in wetlands, while only 5–8% of the world's land is composed of wetlands.[51] Studies have shown that restored wetlands can become productive CO2 sinks[52][53][54] and many are being restored.[55][56] Aside from climate benefits, wetland restoration and conservation can help preserve biodiversity, improve water quality, and aid with flood control.[57]

The plants that makeup wetlands absorb carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere and convert it into organic matter. The waterlogged nature of the soil slows down the decomposition of organic material, leading to the accumulation of carbon-rich peat,[clarification needed] acting as a long-term carbon sink.[58] Also, anaerobic conditions in waterlogged soils hinder the complete breakdown of organic matter, promoting the conversion of carbon into more stable forms.[58][needs copy edit]

As with forests, for the sequestration process to succeed, the wetland must remain undisturbed. If it is disturbed the carbon stored in the plants and sediments will be released back into the atmosphere, and the ecosystem will no longer function as a carbon sink.[59] Additionally, some wetlands can release non-CO2 greenhouse gases, such as methane[60] and nitrous oxide[61] which could offset potential climate benefits. The amounts of carbon sequestered via blue carbon by wetlands can also be difficult to measure.[57]

Wetland soil is an important carbon sink; 14.5% of the world's soil carbon is found in wetlands, while only 5.5% of the world's land is composed of wetlands.[62] Not only are wetlands a great carbon sink, they have many other benefits like collecting floodwater, filtering out air and water pollutants, and creating a home for numerous birds, fish, insects, and plants.[63]

Climate change could alter wetland soil carbon storage, changing it from a sink to a source.[64][obsolete source]With rising temperatures comes an increase in greenhouse gasses from wetlands especially locations with permafrost. When this permafrost melts it increases the available oxygen and water in the soil.[64] Because of this, bacteria in the soil would create large amounts of carbon dioxide and methane to be released into the atmosphere.[64][obsolete source]

The link between climate change and wetlands is still not fully known.[64][obsolete source]It is also not clear how restored wetlands manage carbon while still being a contributing source of methane. However, preserving these areas would help prevent further release of carbon into the atmosphere.[65]

Peatlands, mires and peat bogs

[edit]Despite occupying only 3% of the global land area, peatlands hold approximately 30% of the carbon in our ecosystem - twice the amount stored in the world's forests.[65][66] Most peatlands are situated in high latitude areas of the northern hemisphere, with most of their growth occurring since the last ice age,[67] but they are also found in tropical regions, such as the Amazon and Congo Basin.[68]

Peatlands grow steadily over thousands of years, accumulating dead plant material – and the carbon contained within it – due to waterlogged conditions which greatly slow rates of decay.[67] If peatlands are drained, for farmland or development, the plant material stored within them decomposes rapidly, releasing stored carbon. These degraded peatlands account for 5-10% of global carbon emissions from human activities.[67][69] The loss of one peatland could potentially produce more carbon than 175–500 years of methane emissions.[64]

Peatland protection and restoration are therefore important measures to mitigate carbon emissions, and also provides benefits for biodiversity,[69] freshwater provision, and flood risk reduction.[70]

Agriculture

[edit]

Compared to natural vegetation, cropland soils are depleted in soil organic carbon (SOC). When soil is converted from natural land or semi-natural land, such as forests, woodlands, grasslands, steppes, and savannas, the SOC content in the soil reduces by about 30–40%.[71] This loss is due to harvesting, as plants contain carbon. When land use changes, the carbon in the soil will either increase or decrease, and this change will continue until the soil reaches a new equilibrium. Deviations from this equilibrium can also be affected by variated[clarification needed] climate.[72]

The decreasing of SOC content can be counteracted by increasing the carbon input. This can be done with several strategies, e.g. leave harvest residues on the field, use manure as fertilizer, or include perennial crops in the rotation. Perennial crops have a larger below-ground biomass fraction, which increases the SOC content.[71]

Perennial crops reduce the need for tillage and thus help mitigate soil erosion, and may help increase soil organic matter. Globally, soils are estimated to contain >8,580 gigatons of organic carbon, about ten times the amount in the atmosphere and much more than in vegetation.[73]

Researchers have found that rising temperatures can lead to population booms in soil microbes, converting stored carbon into carbon dioxide. In laboratory experiments heating soil, fungi-rich soils released less carbon dioxide than other soils.[74]

Following carbon dioxide (CO2) absorption from the atmosphere, plants deposit organic matter into the soil.[22] This organic matter, derived from decaying plant material and root systems, is rich in carbon compounds. Microorganisms in the soil break down this organic matter, and in the process, some of the carbon becomes further stabilized in the soil as humus - a process known as humification.[75]

On a global basis, it is estimated that soil contains about 2,500 gigatons of carbon.[contradictory]This is greater than 3-fold the carbon found in the atmosphere and 4-fold of that found in living plants and animals.[76] About 70% of the global soil organic carbon in non-permafrost areas is found in the deeper soil within the upper metre and is stabilized by mineral-organic associations.[77]

Carbon farming

[edit]Carbon farming is a set of agricultural methods that aim to store carbon in the soil, crop roots, wood and leaves. The technical term for this is carbon sequestration. The overall goal of carbon farming is to create a net loss of carbon from the atmosphere.[78] This is done by increasing the rate at which carbon is sequestered into soil and plant material. One option is to increase the soil's organic matter content. This can also aid plant growth, improve soil water retention capacity[79] and reduce fertilizer use.[80] Sustainable forest management is another tool that is used in carbon farming.[81] Carbon farming is one component of climate-smart agriculture. It is also one way to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

Agricultural methods for carbon farming include adjusting how tillage and livestock grazing is done, using organic mulch or compost, working with biochar and terra preta, and changing the crop types. Methods used in forestry include reforestation and bamboo farming.

Carbon farming methods might have additional costs. Some countries have government policies that give financial incentives to farmers to use carbon farming methods.[82] As of 2016, variants of carbon farming reached hundreds of millions of hectares globally, of the nearly 5 billion hectares (1.2×1010 acres) of world farmland.[83] Carbon farming has some disadvantages because some of its methods can affect ecosystem services. For example, carbon farming could cause an increase of land clearing, monocultures and biodiversity loss.[84] It is important to maximize environmental benefits of carbon farming by keeping in mind ecosystem services at the same time.[84]Prairies

[edit]Prairie restoration is a conservation effort to restore prairie lands that were destroyed due to industrial, agricultural, commercial, or residential development.[85] The primary aim is to return areas and ecosystems to their previous state before their depletion.[86] The mass of SOC able to be stored in these restored plots is typically greater than the previous crop, acting as a more effective carbon sink.[87][88]

Biochar

[edit]Biochar is charcoal created by pyrolysis of biomass waste. The resulting material is added to a landfill or used as a soil improver to create terra preta.[89][90] Adding biochar may increase the soil-C stock for the long term and so mitigate global warming by offsetting the atmospheric C (up to 9.5 Gigatons C annually).[91] In the soil, the biochar carbon is unavailable for oxidation to CO

2 and consequential atmospheric release. However concerns have been raised about biochar potentially accelerating release of the carbon already present in the soil.[92][needs update]

Terra preta, an anthropogenic, high-carbon soil, is also being investigated as a sequestration mechanism. By pyrolysing biomass, about half of its carbon can be reduced to charcoal, which can persist in the soil for centuries, and makes a useful soil amendment, especially in tropical soils (biochar or agrichar).[93][94]

Burial of biomass

[edit]

Burying biomass (such as trees) directly mimics the natural processes that created fossil fuels.[95] The global potential for carbon sequestration using wood burial is estimated to be 10 ± 5 GtC/yr and largest rates in tropical forests (4.2 GtC/yr), followed by temperate (3.7 GtC/yr) and boreal forests (2.1 GtC/yr).[14] In 2008, Ning Zeng of the University of Maryland estimated 65 GtC[needs update] lying on the floor of the world's forests as coarse woody material which could be buried and costs for wood burial carbon sequestration run at 50 USD/tC which is much lower than carbon capture from e.g. power plant emissions.[14] CO2 fixation into woody biomass is a natural process carried out through photosynthesis. This is a nature-based solution and methods being trialled include the use of "wood vaults" to store the wood-containing carbon under oxygen-free conditions.[96]

In 2022 a certification organization published methodologies for biomass burial.[97] Other biomass storage proposals have included the burial of biomass deep underwater, including at the bottom of the Black Sea.[98]

Geological carbon sequestration

[edit]Underground storage in suitable geologic formations

[edit]Geological sequestration refers to the storage of CO2 underground in depleted oil and gas reservoirs, saline formations, or deep, coal beds unsuitable for mining.[99]

Once CO2 is captured from a point source, such as a cement factory,[100] it can be compressed to ≈100 bar into a supercritical fluid. In this form, the CO2 could be transported via pipeline to the place of storage. The CO2 could then be injected deep underground, typically around 1 km (0.6 mi), where it would be stable for hundreds to millions of years.[101] Under these storage conditions, the density of supercritical CO2 is 600 to 800 kg/m3.[102]

The important parameters in determining a good site for carbon storage are: rock porosity, rock permeability, absence of faults, and geometry of rock layers. The medium in which the CO2 is to be stored ideally has a high porosity and permeability, such as sandstone or limestone. Sandstone can have a permeability ranging from 1 to 10−5 Darcy, with a porosity as high as ≈30%. The porous rock must be capped by a layer of low permeability which acts as a seal, or caprock, for the CO2. Shale is an example of a very good caprock, with a permeability of 10−5 to 10−9 Darcy. Once injected, the CO2 plume will rise via buoyant forces, since it is less dense than its surroundings. Once it encounters a caprock, it will spread laterally until it encounters a gap. If there are fault planes near the injection zone, there is a possibility the CO2 could migrate along the fault to the surface, leaking into the atmosphere, which would be potentially dangerous to life in the surrounding area. Another risk related to carbon sequestration is induced seismicity. If the injection of CO2 creates pressures underground that are too high, the formation will fracture, potentially causing an earthquake.[103]

Structural trapping is considered the principal storage mechanism, impermeable or low permeability rocks such as mudstone, anhydrite, halite, or tight carbonates[clarification needed] act as a barrier to the upward buoyant migration of CO2, resulting in the retention of CO2 within a storage formation.[104] While trapped in a rock formation, CO2 can be in the supercritical fluid phase or dissolve in groundwater/brine. It can also react with minerals in the geologic formation to become carbonates.

Mineral sequestration

[edit]Mineral sequestration aims to trap carbon in the form of solid carbonate salts. This process occurs slowly in nature and is responsible for the deposition and accumulation of limestone over geologic time. Carbonic acid in groundwater slowly reacts with complex silicates to dissolve calcium, magnesium, alkalis and silica and leave a residue of clay minerals. The dissolved calcium and magnesium react with bicarbonate to precipitate calcium and magnesium carbonates, a process that organisms use to make shells. When the organisms die, their shells are deposited as sediment and eventually turn into limestone. Limestones have accumulated over billions of years of geologic time and contain much of Earth's carbon. Ongoing research aims to speed up similar reactions involving alkali carbonates.[105]

Zeolitic imidazolate frameworks (ZIFs) are metal–organic frameworks similar to zeolites. Because of their porosity, chemical stability and thermal resistance, ZIFs are being examined for their capacity to capture carbon dioxide.[106][needs update]

Mineral carbonation

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (June 2019) |

CO2 exothermically reacts with metal oxides, producing stable carbonates (e.g. calcite, magnesite). This process (CO2-to-stone) occurs naturally over periods of years and is responsible for much surface limestone. Olivine is one such metal oxide.[107][self-published source?] Rocks rich in metal oxides that react with CO2, such as MgO and CaO as contained in basalts, have been proven as a viable means to achieve carbon-dioxide mineral storage.[108][109] The reaction rate can in principle be accelerated with a catalyst[110] or by increasing pressures, or by mineral pre-treatment, although this method can require additional energy.

Ultramafic mine tailings are a readily available source of fine-grained metal oxides that could serve this purpose.[111] Accelerating passive CO2 sequestration via mineral carbonation may be achieved through microbial processes that enhance mineral dissolution and carbonate precipitation.[112][113][114]

Carbon, in the form of CO

2 can be removed from the atmosphere by chemical processes, and stored in stable carbonate mineral forms. This process (CO

2-to-stone) is known as "carbon sequestration by mineral carbonation" or mineral sequestration. The process involves reacting carbon dioxide with abundantly available metal oxides – either magnesium oxide (MgO) or calcium oxide (CaO) – to form stable carbonates. These reactions are exothermic and occur naturally (e.g., the weathering of rock over geologic time periods).[115][116]

- CaO + CO

2 → CaCO

3

- MgO + CO

2 → MgCO

3

Calcium and magnesium are found in nature typically as calcium and magnesium silicates (such as forsterite and serpentinite) and not as binary oxides. For forsterite and serpentine the reactions are:

- Mg

2SiO

4 + 2 CO

2 → 2 MgCO

3 + SiO

2

- Mg

3Si

2O

5(OH)

4+ 3 CO

2 → 3 MgCO

3 + 2 SiO

2 + 2 H

2O

These reactions are slightly more favorable at low temperatures.[115] This process occurs naturally over geologic time frames and is responsible for much of the Earth's surface limestone. The reaction rate can be made faster however, by reacting at higher temperatures and/or pressures, although this method requires some additional energy. Alternatively, the mineral could be milled to increase its surface area, and exposed to water and constant abrasion to remove the inert silica as could be achieved naturally by dumping olivine in the high energy surf of beaches.[117]

When CO

2 is dissolved in water and injected into hot basaltic rocks underground it has been shown that the CO

2 reacts with the basalt to form solid carbonate minerals.[118] A test plant in Iceland started up in October 2017, extracting up to 50 tons of CO2 a year from the atmosphere and storing it underground in basaltic rock.[119][needs update]

Sequestration in oceans

[edit]Marine carbon pumps

[edit]

The ocean naturally sequesters carbon through different processes.[120] The solubility pump moves carbon dioxide from the atmosphere into the surface ocean where it reacts with water molecules to form carbonic acid. The solubility of carbon dioxide increases with decreasing water temperatures. Thermohaline circulation moves dissolved carbon dioxide to cooler waters where it is more soluble, increasing carbon concentrations in the ocean interior. The biological pump moves dissolved carbon dioxide from the surface ocean to the ocean's interior through the conversion of inorganic carbon to organic carbon by photosynthesis. Organic matter that survives respiration and remineralization can be transported through sinking particles and organism migration to the deep ocean.[citation needed]

The low temperatures, high pressure, and reduced oxygen levels in the deep sea slow down decomposition processes, preventing the rapid release of carbon back into the atmosphere and acting as a long-term storage reservoir.[121]

Vegetated coastal ecosystems

[edit]Seaweed farming and algae

[edit]

Seaweed grow in shallow and coastal areas, and capture significant amounts of carbon that can be transported to the deep ocean by oceanic mechanisms; seaweed reaching the deep ocean sequester carbon and prevent it from exchanging with the atmosphere over millennia.[123] Growing seaweed offshore with the purpose of sinking the seaweed in the depths of the sea to sequester carbon has been suggested.[124] In addition, seaweed grows very fast and can theoretically be harvested and processed to generate biomethane, via anaerobic digestion to generate electricity, via cogeneration/CHP or as a replacement for natural gas. One study suggested that if seaweed farms covered 9% of the ocean they could produce enough biomethane to supply Earth's equivalent demand for fossil fuel energy, remove 53 gigatonnes of CO2 per year from the atmosphere and sustainably produce 200 kg per year of fish, per person, for 10 billion people.[125][obsolete source]Ideal species for such farming and conversion include Laminaria digitata, Fucus serratus and Saccharina latissima.[126]

Both macroalgae and microalgae are being investigated as possible means of carbon sequestration.[127][128] Marine phytoplankton perform half of the global photosynthetic CO2 fixation (net global primary production of ~50 Pg C per year) and half of the oxygen production despite amounting to only ~1% of global plant biomass.[129]

Because algae lack the complex lignin associated with terrestrial plants, the carbon in algae is released into the atmosphere more rapidly than carbon captured on land.[127][130] Algae have been proposed as a short-term storage pool of carbon that can be used as a feedstock for the production of various biogenic fuels.[131]

Large-scale seaweed farming could sequester significant amounts of carbon.[6] Wild seaweed will sequester large amount of carbon through dissolved particles of organic matter being transported to deep ocean seafloors where it will become buried and remain for long periods of time.[7] With respect to carbon farming, the potential growth of seaweed for carbon farming would see the harvested seaweed transported to the deep ocean for long-term burial.[7] Seaweed farming occurs mostly in the Asian Pacific coastal areas where it has been a rapidly increasing market.[7] The IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate recommends "further research attention" on seaweed farming as a mitigation tactic.[8]

Ocean fertilization

[edit]

Ocean fertilization or ocean nourishment is a type of technology for carbon dioxide removal from the ocean based on the purposeful introduction of plant nutrients to the upper ocean to increase marine food production and to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.[132][133] Ocean nutrient fertilization, for example iron fertilization, could stimulate photosynthesis in phytoplankton. The phytoplankton would convert the ocean's dissolved carbon dioxide into carbohydrate, some of which would sink into the deeper ocean before oxidizing. More than a dozen open-sea experiments confirmed that adding iron to the ocean increases photosynthesis in phytoplankton by up to 30 times.[134]

This is one of the more well-researched carbon dioxide removal (CDR) approaches, and supported by the Climate restoration proponents. However, there is uncertainty about this approach regarding the duration of the effective oceanic carbon sequestration. While surface ocean acidity may decrease as a result of nutrient fertilization, when the sinking organic matter remineralizes, deep ocean acidity could increase. A 2021 report on CDR indicates that there is medium-high confidence that the technique could be efficient and scalable at low cost, with medium environmental risks.[135] The risks of nutrient fertilization can be monitored. Peter Fiekowsy and Carole Douglis write "I consider iron fertilization an important item on our list of pottential climate restoration solutions. Given the fact that iron fertilization is a natural process that has taken place on a massive scale for millions of years, it is likely that most of the side effects are familiar ones that pose no major threat" [136]

A number of techniques, including fertilization by the micronutrient iron (called iron fertilization) or with nitrogen and phosphorus (both macronutrients), have been proposed. Some research in the early 2020s suggested that it could only permanently sequester a small amount of carbon.[137] More recent research publlications sustain that iron fertilization shows promise. A NOAA special report rated iron fertilization as having "a moderate potential for cost, scalability and how long carbon might be stored compared to other marine sequestration ideas" [138]Artificial upwelling

[edit]Artificial upwelling or downwelling is an approach that would change the mixing layers of the ocean. Encouraging various ocean layers to mix can move nutrients and dissolved gases around.[139] Mixing may be achieved by placing large vertical pipes in the oceans to pump nutrient rich water to the surface, triggering blooms of algae, which store carbon when they grow and export[clarification needed] carbon when they die.[139][140][141] This produces results somewhat similar to iron fertilization. One side-effect is a short-term rise in CO

2, which limits its attractiveness.[142]

Mixing layers involve transporting the denser and colder deep ocean water to the surface mixed layer. As the ocean temperature decreases with depth, more carbon dioxide and other compounds are able to dissolve in the deeper layers.[143] This can be induced by reversing the oceanic carbon cycle through the use of large vertical pipes serving as ocean pumps,[144] or a mixer array.[145] When the nutrient rich deep ocean water is moved to the surface, algae bloom occurs, resulting in a decrease in carbon dioxide due to carbon intake from phytoplankton and other photosynthetic eukaryotic organisms. The transfer of heat between the layers will also cause seawater from the mixed layer to sink and absorb more carbon dioxide. This method has not gained much traction as algae bloom harms marine ecosystems by blocking sunlight and releasing harmful toxins into the ocean.[146] The sudden increase in carbon dioxide on the surface level will also temporarily decrease the pH of the seawater, impairing the growth of coral reefs. The production of carbonic acid through the dissolution of carbon dioxide in seawater hinders marine biogenic calcification and causes major disruptions to the oceanic food chain.[147]

Basalt storage

[edit]Carbon dioxide sequestration in basalt involves the injecting of CO

2 into deep-sea formations. The CO

2 first mixes with seawater and then reacts with the basalt, both of which are alkaline-rich elements. This reaction results in the release of Ca2+ and Mg2+ ions forming stable carbonate minerals.[148]

Underwater basalt offers a good alternative to other forms of oceanic carbon storage because it has a number of trapping measures to ensure added protection against leakage. These measures include "geochemical, sediment, gravitational and hydrate formation." Because CO

2 hydrate is denser than CO

2 in seawater, the risk of leakage is minimal. Injecting the CO

2 at depths greater than 2,700 meters (8,900 ft) ensures that the CO

2 has a greater density than seawater, causing it to sink.[149]

One possible injection site is Juan de Fuca Plate. Researchers at the Lamont–Doherty Earth Observatory found that this plate at the western coast of the United States has a possible storage capacity of 208 gigatons. This could cover the entire current U.S. carbon emissions for over 100 years (as of 2009).[149]

This process is undergoing tests as part of the CarbFix project, resulting in 95% of the injected 250 tonnes of CO2 to solidify into calcite in two years, using 25 tonnes of water per tonne of CO2.[150][151][needs update]

Mineralization and deep sea sediments

[edit]Similar to mineralization processes that take place within rocks, mineralization can also occur under the sea. The rate of dissolution of carbon dioxide from atmosphere to oceanic regions[clarification needed] is determined by the circulation period of the ocean and buffering ability of subducting surface water.[152] Researchers have demonstrated that the carbon dioxide marine storage at several kilometers depth could be viable for up to 500 years, but is dependent on injection site and conditions. Several studies have shown that although it may fix carbon dioxide effectively, carbon dioxide may be released back to the atmosphere over time. However, this is unlikely for at least a few more centuries. The neutralization of CaCO3, or balancing the concentration of CaCO3 on the seafloor, land and in the ocean, can be measured on a timescale of thousands of years. More specifically, the predicted time is 1700 years for ocean and approximately 5000 to 6000 years for land.[153][154] Further, the dissolution time for CaCO3 can be improved by injecting near or downstream of the storage site.[155]

In addition to carbon mineralization, another proposal is deep sea sediment injection. It injects liquid carbon dioxide at least 3,000 m (9,800 ft) below the surface directly into ocean sediments to generate carbon dioxide hydrate. Two regions are defined for exploration: 1) the negative buoyancy zone (NBZ), which is the region between liquid carbon dioxide denser than surrounding water and where liquid carbon dioxide has neutral buoyancy, and 2) the hydrate formation zone (HFZ), which typically has low temperatures and high pressures. Several research models have shown that the optimal depth of injection requires consideration of intrinsic permeability and any changes in liquid carbon dioxide permeability for optimal storage. The formation of hydrates decreases liquid carbon dioxide permeability, and injection below HFZ is more energetically favored than within the HFZ. If the NBZ is a greater column of water than the HFZ, the injection should happen below the HFZ and directly to the NBZ.[156] In this case, liquid carbon dioxide will sink to the NBZ and be stored below the buoyancy and hydrate cap. Carbon dioxide leakage can occur if there is dissolution into pore fluid[clarification needed]or via molecular diffusion. However, this occurs over thousands of years.[155][157][158]

Adding bases to neutralize acids

[edit]Carbon dioxide forms carbonic acid when dissolved in water, so ocean acidification is a significant consequence of elevated carbon dioxide levels, and limits the rate at which it can be absorbed into the ocean (the solubility pump). A variety of different bases have been suggested that could neutralize the acid and thus increase CO

2 absorption.[159][160][161][162][163] For example, adding crushed limestone to oceans enhances the absorption of carbon dioxide.[164] Another approach is to add sodium hydroxide to oceans which is produced by electrolysis of salt water or brine, while eliminating the waste hydrochloric acid by reaction with a volcanic silicate rock such as enstatite, effectively increasing the rate of natural weathering of these rocks to restore ocean pH.[165][166][167][needs copy edit]

Single-step carbon sequestration and storage

[edit]Single-step carbon sequestration and storage is a saline water-based mineralization technology extracting carbon dioxide from seawater and storing it in the form of solid minerals.[168]

Abandoned ideas

[edit]Direct deep-sea carbon dioxide injection

[edit]It was once suggested that CO2 could be stored in the oceans by direct injection into the deep ocean and storing it there for some centuries. At the time, this proposal was called "ocean storage" but more precisely it was known as "direct deep-sea carbon dioxide injection". However, the interest in this avenue of carbon storage has much reduced since about 2001 because of concerns about the unknown impacts on marine life[169]: 279 , high costs and concerns about its stability or permanence.[101] The "IPCC Special Report on Carbon Dioxide Capture and Storage" in 2005 did include this technology as an option.[169]: 279 However, the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report in 2014 no longer mentioned the term "ocean storage" in its report on climate change mitigation methods.[170] The most recent IPCC Sixth Assessment Report in 2022 also no longer includes any mention of "ocean storage" in its "Carbon Dioxide Removal taxonomy".[171]: 12–37

Costs

[edit]Cost of carbon sequestration (not including capture and transport) varies but is below US$10 per tonne in some cases where onshore storage is available.[172] For example Carbfix cost is around US$25 per tonne of CO2.[173] A 2020 report estimated sequestration in forests (so including capture) at US$35 for small quantities to US$280 per tonne for 10% of the total required to keep to 1.5 C warming.[174] But there is risk of forest fires releasing the carbon.[175]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "CCS Explained". UKCCSRC. Archived from the original on June 28, 2020. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- ^ IPCC (2021). Masson-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P.; Pirani, A.; Connors, S. L.; et al. (eds.). Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis (PDF). Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press (In Press). Archived (PDF) from the original on June 5, 2022. Retrieved June 3, 2022.

- ^ a b "What is carbon sequestration? | U.S. Geological Survey". www.usgs.gov. Archived from the original on February 6, 2023. Retrieved February 6, 2023.

- ^ Myles, Allen (September 2020). "The Oxford Principles for Net Zero Aligned Carbon Offsetting" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 2, 2020. Retrieved December 10, 2021.

- ^ Renforth, Phil; Henderson, Gideon (June 15, 2017). "Assessing ocean alkalinity for carbon sequestration". Reviews of Geophysics. 55 (3): 636–674. Bibcode:2017RvGeo..55..636R. doi:10.1002/2016RG000533. S2CID 53985208. Retrieved March 3, 2024.

- ^ a b Duarte, Carlos M.; Wu, Jiaping; Xiao, Xi; Bruhn, Annette; Krause-Jensen, Dorte (2017). "Can Seaweed Farming Play a Role in Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation?". Frontiers in Marine Science. 4. doi:10.3389/fmars.2017.00100. ISSN 2296-7745.

- ^ a b c d Froehlich, Halley E.; Afflerbach, Jamie C.; Frazier, Melanie; Halpern, Benjamin S. (September 23, 2019). "Blue Growth Potential to Mitigate Climate Change through Seaweed Offsetting". Current Biology. 29 (18): 3087–3093.e3. Bibcode:2019CBio...29E3087F. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.07.041. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 31474532.

- ^ a b Bindoff, N. L.; Cheung, W. W. L.; Kairo, J. G.; Arístegui, J.; et al. (2019). "Chapter 5: Changing Ocean, Marine Ecosystems, and Dependent Communities" (PDF). IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate. pp. 447–587. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 28, 2020. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ a b c Warner, Emily; Cook-Patton, Susan C.; Lewis, Owen T.; Brown, Nick; Koricheva, Julia; Eisenhauer, Nico; Ferlian, Olga; Gravel, Dominique; Hall, Jefferson S.; Jactel, Hervé; Mayoral, Carolina; Meredieu, Céline; Messier, Christian; Paquette, Alain; Parker, William C. (2023). "Young mixed planted forests store more carbon than monocultures—a meta-analysis". Frontiers in Forests and Global Change. 6. Bibcode:2023FrFGC...626514W. doi:10.3389/ffgc.2023.1226514. ISSN 2624-893X.

- ^ IPCC, 2021: Annex VII: Glossary Archived June 5, 2022, at the Wayback Machine [Matthews, J.B.R., V. Möller, R. van Diemen, J.S. Fuglestvedt, V. Masson-Delmotte, C. Méndez, S. Semenov, A. Reisinger (eds.)]. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Archived August 9, 2021, at the Wayback Machine [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, US, pp. 2215–2256, doi:10.1017/9781009157896.022.

- ^ Myles, Allen (September 2020). "The Oxford Principles for Net Zero Aligned Carbon Offsetting" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 2, 2020. Retrieved December 10, 2021.

- ^ Hodrien, Chris (October 24, 2008). Squaring the Circle on Coal – Carbon Capture and Storage. Claverton Energy Group Conference, Bath. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 31, 2009. Retrieved May 9, 2010.

- ^ Bui, Mai; Adjiman, Claire S.; Bardow, André; Anthony, Edward J.; Boston, Andy; Brown, Solomon; Fennell, Paul S.; Fuss, Sabine; Galindo, Amparo; Hackett, Leigh A.; Hallett, Jason P.; Herzog, Howard J.; Jackson, George; Kemper, Jasmin; Krevor, Samuel (2018). "Carbon capture and storage (CCS): the way forward". Energy & Environmental Science. 11 (5): 1062–1176. doi:10.1039/C7EE02342A. hdl:10044/1/55714. ISSN 1754-5692. Archived from the original on March 17, 2023. Retrieved February 6, 2023.

- ^ a b c Ning Zeng (2008). "Carbon sequestration via wood burial". Carbon Balance and Management. 3 (1): 1. Bibcode:2008CarBM...3....1Z. doi:10.1186/1750-0680-3-1. PMC 2266747. PMID 18173850.

- ^ "Executive Order on Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad". The White House. January 27, 2021. Archived from the original on February 17, 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- ^ Beerling, David (2008). The Emerald Planet: How Plants Changed Earth's History. Oxford University Press. pp. 194–5. ISBN 978-0-19-954814-9.

- ^ National Academies Of Sciences, Engineering (2019). Negative Emissions Technologies and Reliable Sequestration: A Research Agenda. Washington, D.C.: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. pp. 45–136. doi:10.17226/25259. ISBN 978-0-309-48452-7. PMID 31120708. S2CID 134196575.

- ^ *IPCC (2022). "Summary for Policymakers" (PDF). Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 7, 2022. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- ^ "World Soil Resources Reports" (PDF). Retrieved December 19, 2023.

- ^ a b Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020. FAO. 2020. doi:10.4060/ca8753en. ISBN 978-92-5-132581-0. S2CID 130116768.

- ^ IPCC (2022) Summary for policy makers in Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA

- ^ a b Sedjo, R., & Sohngen, B. (2012). Carbon sequestration in forests and soils. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ., 4(1), 127-144.

- ^ Baccini, A.; Walker, W.; Carvalho, L.; Farina, M.; Sulla-Menashe, D.; Houghton, R. A. (October 2017). "Tropical forests are a net carbon source based on aboveground measurements of gain and loss". Science. 358 (6360): 230–234. Bibcode:2017Sci...358..230B. doi:10.1126/science.aam5962. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 28971966.

- ^ Spawn, Seth A.; Sullivan, Clare C.; Lark, Tyler J.; Gibbs, Holly K. (April 6, 2020). "Harmonized global maps of above and belowground biomass carbon density in the year 2010". Scientific Data. 7 (1): 112. Bibcode:2020NatSD...7..112S. doi:10.1038/s41597-020-0444-4. ISSN 2052-4463. PMC 7136222. PMID 32249772.

- ^ Carolyn Gramling (September 28, 2017). "Tropical forests have flipped from sponges to sources of carbon dioxide; A closer look at the world's trees reveals a loss of density in the tropics". Sciencenews.org. 358 (6360): 230–234. Bibcode:2017Sci...358..230B. doi:10.1126/science.aam5962. PMID 28971966. Retrieved October 6, 2017.

- ^ Harvey, Fiona (March 4, 2020). "Tropical forests losing their ability to absorb carbon, study finds". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved March 5, 2020.

- ^ "Press corner". European Commission – European Commission. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- ^ Walker, Xanthe J.; Baltzer, Jennifer L.; Cumming, Steven G.; Day, Nicola J.; Ebert, Christopher; Goetz, Scott; Johnstone, Jill F.; Potter, Stefano; Rogers, Brendan M.; Schuur, Edward A. G.; Turetsky, Merritt R.; Mack, Michelle C. (August 2019). "Increasing wildfires threaten historic carbon sink of boreal forest soils". Nature. 572 (7770): 520–523. Bibcode:2019Natur.572..520W. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1474-y. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 31435055. S2CID 201124728. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- ^ "Climate emissions from tropical forest damage 'underestimated by a factor of six'". The Guardian. October 31, 2019. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- ^ "Why Keeping Mature Forests Intact Is Key to the Climate Fight". Yale E360. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- ^ "Would a Large-scale Reforestation Effort Help Counter the Global Warming Impacts of Deforestation?". Union of Concerned Scientists. September 1, 2012. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- ^ "Planting trees is no substitute for natural forests". phys.org. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

- ^ McDermott, Matthew (August 22, 2008). "Can Aerial Reforestation Help Slow Climate Change? Discovery Project Earth Examines Re-Engineering the Planet's Possibilities". TreeHugger. Archived from the original on March 30, 2010. Retrieved May 9, 2010.

- ^ Lefebvre, David; Williams, Adrian G.; Kirk, Guy J. D.; Paul; Burgess, J.; Meersmans, Jeroen; Silman, Miles R.; Román-Dañobeytia, Francisco; Farfan, Jhon; Smith, Pete (October 7, 2021). "Assessing the carbon capture potential of a reforestation project". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 19907. Bibcode:2021NatSR..1119907L. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-99395-6. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 8497602. PMID 34620924.

- ^ Gorte, Ross W. (2009). Carbon Sequestration in Forests (PDF) (RL31432 ed.). Congressional Research Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 14, 2022. Retrieved January 9, 2023.

- ^ a b c Bastin, Jean-Francois; Finegold, Yelena; Garcia, Claude; Mollicone, Danilo; Rezende, Marcelo; Routh, Devin; Zohner, Constantin M.; Crowther, Thomas W. (July 5, 2019). "The global tree restoration potential". Science. 365 (6448): 76–79. Bibcode:2019Sci...365...76B. doi:10.1126/science.aax0848. PMID 31273120. S2CID 195804232.

- ^ Tutton, Mark (July 4, 2019). "Restoring forests could capture two-thirds of the carbon humans have added to the atmosphere". CNN. Archived from the original on March 23, 2020. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ J. Chatellier (January 2010). The Role of Forest Products in the Global Carbon Cycle: From In-Use to End-of-Life (PDF). Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2010.

- ^ Harmon, M. E.; Harmon, J. M.; Ferrell, W. K.; Brooks, D. (1996). "Modeling carbon stores in Oregon and Washington forest products: 1900?1992". Climatic Change. 33 (4): 521. Bibcode:1996ClCh...33..521H. doi:10.1007/BF00141703. S2CID 27637103.

- ^ Toussaint, Kristin (January 27, 2020). "Building with timber instead of steel could help pull millions of tons of carbon from the atmosphere". Fast Company. Archived from the original on January 28, 2020. Retrieved January 29, 2020.

- ^ Churkina, Galina; Organschi, Alan; Reyer, Christopher P. O.; Ruff, Andrew; Vinke, Kira; Liu, Zhu; Reck, Barbara K.; Graedel, T. E.; Schellnhuber, Hans Joachim (January 27, 2020). "Buildings as a global carbon sink". Nature Sustainability. 3 (4): 269–276. Bibcode:2020NatSu...3..269C. doi:10.1038/s41893-019-0462-4. ISSN 2398-9629. S2CID 213032074. Archived from the original on January 28, 2020. Retrieved January 29, 2020.

- ^ Devi, Angom Sarjubala; Singh, Kshetrimayum Suresh (January 12, 2021). "Carbon storage and sequestration potential in aboveground biomass of bamboos in North East India". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 837. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-80887-w. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 7803772. PMID 33437001.

- ^ "Does harvesting in Canada's forests contribute to climate change?" (PDF). Canadian Forest Service Science-Policy Notes. Natural Resources Canada. May 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 30, 2013.

- ^ "Climate information relevant for Forestry" (PDF).

- ^ Ometto, J.P., K. Kalaba, G.Z. Anshari, N. Chacón, A. Farrell, S.A. Halim, H. Neufeldt, and R. Sukumar, 2022: CrossChapter Paper 7: Tropical Forests. In: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, pp. 2369–2410, doi:10.1017/9781009325844.024.

- ^ Canadell, J.G.; M.R. Raupach (June 13, 2008). "Managing Forests for Climate Change" (PDF). Science. 320 (5882): 1456–1457. Bibcode:2008Sci...320.1456C. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.573.5230. doi:10.1126/science.1155458. PMID 18556550. S2CID 35218793.

- ^ Adam, David (February 18, 2009). "Fifth of world carbon emissions soaked up by extra forest growth, scientists find". The Guardian. London. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ^ Pendleton, Linwood; Donato, Daniel C.; Murray, Brian C.; Crooks, Stephen; Jenkins, W. Aaron; Sifleet, Samantha; Craft, Christopher; Fourqurean, James W.; Kauffman, J. Boone (2012). "Estimating Global "Blue Carbon" Emissions from Conversion and Degradation of Vegetated Coastal Ecosystems". PLOS ONE. 7 (9): e43542. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...743542P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0043542. PMC 3433453. PMID 22962585.

- ^ US EPA, OW (July 27, 2018). "Basic Information about Wetland Restoration and Protection". US EPA. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- ^ a b US Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. "What is Blue Carbon?". oceanservice.noaa.gov. Archived from the original on April 22, 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- ^ Mitsch, William J.; Bernal, Blanca; Nahlik, Amanda M.; Mander, Ülo; Zhang, Li; Anderson, Christopher J.; Jørgensen, Sven E.; Brix, Hans (April 1, 2013). "Wetlands, carbon, and climate change". Landscape Ecology. 28 (4): 583–597. Bibcode:2013LaEco..28..583M. doi:10.1007/s10980-012-9758-8. ISSN 1572-9761. S2CID 11939685.

- ^ Valach, Alex C.; Kasak, Kuno; Hemes, Kyle S.; Anthony, Tyler L.; Dronova, Iryna; Taddeo, Sophie; Silver, Whendee L.; Szutu, Daphne; Verfaillie, Joseph; Baldocchi, Dennis D. (March 25, 2021). "Productive wetlands restored for carbon sequestration quickly become net CO2 sinks with site-level factors driving uptake variability". PLOS ONE. 16 (3): e0248398. Bibcode:2021PLoSO..1648398V. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0248398. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 7993764. PMID 33765085.

- ^ Bu, Xiaoyan; Cui, Dan; Dong, Suocheng; Mi, Wenbao; Li, Yu; Li, Zhigang; Feng, Yaliang (January 2020). "Effects of Wetland Restoration and Conservation Projects on Soil Carbon Sequestration in the Ningxia Basin of the Yellow River in China from 2000 to 2015". Sustainability. 12 (24): 10284. doi:10.3390/su122410284.

- ^ Badiou, Pascal; McDougal, Rhonda; Pennock, Dan; Clark, Bob (June 1, 2011). "Greenhouse gas emissions and carbon sequestration potential in restored wetlands of the Canadian prairie pothole region". Wetlands Ecology and Management. 19 (3): 237–256. Bibcode:2011WetEM..19..237B. doi:10.1007/s11273-011-9214-6. ISSN 1572-9834. S2CID 30476076.

- ^ "Restoring Wetlands - Wetlands (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- ^ "A new partnership for wetland restoration | ICPDR – International Commission for the Protection of the Danube River". www.icpdr.org. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- ^ a b "Fact Sheet: Blue Carbon". American University. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- ^ a b Harris, L. I., Richardson, K., Bona, K. A., Davidson, S. J., Finkelstein, S. A., Garneau, M., ... & Ray, J. C. (2022). The essential carbon service provided by northern peatlands. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 20(4), 222-230.

- ^ "Carbon Sequestration in Wetlands | MN Board of Water, Soil Resources". bwsr.state.mn.us. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- ^ Bridgham, Scott D.; Cadillo-Quiroz, Hinsby; Keller, Jason K.; Zhuang, Qianlai (May 2013). "Methane emissions from wetlands: biogeochemical, microbial, and modeling perspectives from local to global scales". Global Change Biology. 19 (5): 1325–1346. Bibcode:2013GCBio..19.1325B. doi:10.1111/gcb.12131. PMID 23505021. S2CID 14228726. Archived from the original on January 20, 2023. Retrieved January 5, 2023.

- ^ Thomson, Andrew J.; Giannopoulos, Georgios; Pretty, Jules; Baggs, Elizabeth M.; Richardson, David J. (May 5, 2012). "Biological sources and sinks of nitrous oxide and strategies to mitigate emissions". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 367 (1593): 1157–1168. doi:10.1098/rstb.2011.0415. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 3306631. PMID 22451101.

- ^ US EPA, ORD (November 2, 2017). "Wetlands". US EPA. Archived from the original on February 9, 2023. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ "Wetlands". United States Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original on October 20, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Zedler, Joy B.; Kercher, Suzanne (November 21, 2005). "WETLAND RESOURCES: Status, Trends, Ecosystem Services, and Restorability". Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 30 (1): 39–74. doi:10.1146/annurev.energy.30.050504.144248. ISSN 1543-5938.

- ^ a b "The Peatland Ecosystem: The Planet's Most Efficient Natural Carbon Sink". WorldAtlas. August 2017. Archived from the original on February 9, 2023. Retrieved April 3, 2020.

- ^ IUCN UK Peatland Programme. "About Peatlands". IUCN Peatland Programme. Retrieved September 11, 2024.

- ^ a b c Loisel, J.; Gallego-Sala, A. V.; Amesbury, M. J.; Magnan, G.; Anshari, G.; Beilman, D. W.; Benavides, J. C.; Blewett, J.; Camill, P.; Charman, D. J.; Chawchai, S.; Hedgpeth, A.; Kleinen, T.; Korhola, A.; Large, D. (January 2021). "Expert assessment of future vulnerability of the global peatland carbon sink". Nature Climate Change. 11 (1): 70–77. Bibcode:2021NatCC..11...70L. doi:10.1038/s41558-020-00944-0. ISSN 1758-678X.

- ^ Ribeiro, Kelly; Pacheco, Felipe S.; Ferreira, José W.; de Sousa-Neto, Eráclito R.; Hastie, Adam; Krieger Filho, Guenther C.; Alvalá, Plínio C.; Forti, Maria C.; Ometto, Jean P. (December 4, 2020). "Tropical peatlands and their contribution to the global carbon cycle and climate change". Global Change Biology. 27 (3): 489–505. doi:10.1111/gcb.15408. hdl:20.500.11820/98ca9a07-f1be-4808-aa55-8dc7ebb5072b. ISSN 1354-1013. PMID 33070397.

- ^ a b Leifeld, J.; Menichetti, L. (March 14, 2018). "The underappreciated potential of peatlands in global climate change mitigation strategies". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 1071. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9.1071L. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-03406-6. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 5851997. PMID 29540695.

- ^ Strack, Maria; Davidson, Scott J.; Hirano, Takashi; Dunn, Christian (June 13, 2022). "The Potential of Peatlands as Nature-Based Climate Solutions". Current Climate Change Reports. 8 (3): 71–82. Bibcode:2022CCCR....8...71S. doi:10.1007/s40641-022-00183-9. ISSN 2198-6061.

- ^ a b Poeplau, Christopher; Don, Axel (February 1, 2015). "Carbon sequestration in agricultural soils via cultivation of cover crops – A meta-analysis". Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment. 200 (Supplement C): 33–41. Bibcode:2015AgEE..200...33P. doi:10.1016/j.agee.2014.10.024.

- ^ Goglio, Pietro; Smith, Ward N.; Grant, Brian B.; Desjardins, Raymond L.; McConkey, Brian G.; Campbell, Con A.; Nemecek, Thomas (October 1, 2015). "Accounting for soil carbon changes in agricultural life cycle assessment (LCA): a review". Journal of Cleaner Production. 104: 23–39. Bibcode:2015JCPro.104...23G. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.05.040. ISSN 0959-6526. Archived from the original on October 30, 2020. Retrieved November 27, 2017.

- ^ Blakemore, R.J. (November 2018). "Non-flat Earth Recalibrated for Terrain and Topsoil". Soil Systems. 2 (4): 64. doi:10.3390/soilsystems2040064.

- ^ Kreier, Freda (November 30, 2021). "Fungi may be crucial to storing carbon in soil as the Earth warms". Science News. Archived from the original on November 30, 2021. Retrieved December 1, 2021.

- ^ Guggenberger, G. (2005). Humification and mineralization in soils. In Microorganisms in soils: roles in genesis and functions (pp. 85-106). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- ^ "Soil carbon: what we've learned so far". Cawood. Archived from the original on January 20, 2023. Retrieved January 20, 2023.

- ^ Georgiou, Katerina; Jackson, Robert B.; Vindušková, Olga; Abramoff, Rose Z.; Ahlström, Anders; Feng, Wenting; Harden, Jennifer W.; Pellegrini, Adam F. A.; Polley, H. Wayne; Soong, Jennifer L.; Riley, William J.; Torn, Margaret S. (July 1, 2022). "Global stocks and capacity of mineral-associated soil organic carbon". Nature Communications. 13 (1): 3797. Bibcode:2022NatCo..13.3797G. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-31540-9. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 9249731. PMID 35778395.

- ^ Nath, Arun Jyoti; Lal, Rattan; Das, Ashesh Kumar (January 1, 2015). "Managing woody bamboos for carbon farming and carbon trading". Global Ecology and Conservation. 3: 654–663. Bibcode:2015GEcoC...3..654N. doi:10.1016/j.gecco.2015.03.002. ISSN 2351-9894.

- ^ "Carbon Farming | Carbon Cycle Institute". www.carboncycle.org. Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ^ Almaraz, Maya; Wong, Michelle Y.; Geoghegan, Emily K.; Houlton, Benjamin Z. (2021). "A review of carbon farming impacts on nitrogen cycling, retention, and loss". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1505 (1): 102–117. Bibcode:2021NYASA1505..102A. doi:10.1111/nyas.14690. ISSN 0077-8923. S2CID 238202676.

- ^ Jindal, Rohit; Swallow, Brent; Kerr, John (2008). "Forestry-based carbon sequestration projects in Africa: Potential benefits and challenges". Natural Resources Forum. 32 (2): 116–130. doi:10.1111/j.1477-8947.2008.00176.x. ISSN 1477-8947.

- ^ Tang, Kai; Kragt, Marit E.; Hailu, Atakelty; Ma, Chunbo (May 1, 2016). "Carbon farming economics: What have we learned?". Journal of Environmental Management. 172: 49–57. Bibcode:2016JEnvM.172...49T. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.02.008. ISSN 0301-4797. PMID 26921565.

- ^ Burton, David. "How carbon farming can help solve climate change". The Conversation. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ^ a b Lin, Brenda B.; Macfadyen, Sarina; Renwick, Anna R.; Cunningham, Saul A.; Schellhorn, Nancy A. (October 1, 2013). "Maximizing the Environmental Benefits of Carbon Farming through Ecosystem Service Delivery". BioScience. 63 (10): 793–803. doi:10.1525/bio.2013.63.10.6. ISSN 0006-3568.

- ^ "Restoration". Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved April 6, 2023.

- ^ Allison, Stuart K. (2004). "What "Do" We Mean When We Talk About Ecological Restoration?". Ecological Restoration. 22 (4): 281–286. doi:10.3368/er.22.4.281. ISSN 1543-4060. JSTOR 43442777. S2CID 84987493.

- ^ Nelson, J. D. J.; Schoenau, J. J.; Malhi, S. S. (October 1, 2008). "Soil organic carbon changes and distribution in cultivated and restored grassland soils in Saskatchewan". Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems. 82 (2): 137–148. Bibcode:2008NCyAg..82..137N. doi:10.1007/s10705-008-9175-1. ISSN 1573-0867. S2CID 24021984.

- ^ Anderson-Teixeira, Kristina J.; Davis, Sarah C.; Masters, Michael D.; Delucia, Evan H. (February 2009). "Changes in soil organic carbon under biofuel crops". GCB Bioenergy. 1 (1): 75–96. Bibcode:2009GCBBi...1...75A. doi:10.1111/j.1757-1707.2008.01001.x. S2CID 84636376.

- ^ Lehmann, J.; Gaunt, J.; Rondon, M. (2006). "Bio-char sequestration in terrestrial ecosystems – a review" (PDF). Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change (Submitted manuscript). 11 (2): 403–427. Bibcode:2006MASGC..11..403L. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.183.1147. doi:10.1007/s11027-005-9006-5. S2CID 4696862. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 25, 2018. Retrieved July 31, 2018.

- ^ "International Biochar Initiative | International Biochar Initiative". Biochar-international.org. Archived from the original on May 5, 2012. Retrieved May 9, 2010.

- ^ Yousaf, Balal; Liu, Guijian; Wang, Ruwei; Abbas, Qumber; Imtiaz, Muhammad; Liu, Ruijia (2016). "Investigating the biochar effects on C-mineralization and sequestration of carbon in soil compared with conventional amendments using stable isotope (δ13C) approach". GCB Bioenergy. 9 (6): 1085–1099. doi:10.1111/gcbb.12401.

- ^ Wardle, David A.; Nilsson, Marie-Charlotte; Zackrisson, Olle (May 2, 2008). "Fire-Derived Charcoal Causes Loss of Forest Humus". Science. 320 (5876): 629. Bibcode:2008Sci...320..629W. doi:10.1126/science.1154960. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 18451294. S2CID 22192832. Archived from the original on August 8, 2021. Retrieved August 8, 2021.

- ^ Johannes Lehmann. "Biochar: the new frontier". Archived from the original on June 18, 2008. Retrieved July 8, 2008.

- ^ Horstman, Mark (September 23, 2007). "Agrichar – A solution to global warming?". ABC TV Science: Catalyst. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on April 30, 2019. Retrieved July 8, 2008.

- ^ Lovett, Richard (May 3, 2008). "Burying biomass to fight climate change". New Scientist (2654). Archived from the original on August 3, 2009. Retrieved May 9, 2010.

- ^ "A stealth effort to bury wood for carbon removal has just raised millions". MIT Technology Review. Retrieved May 5, 2024.

- ^ "A deceptively simple technology for carbon removal | GreenBiz". www.greenbiz.com. March 13, 2023. Retrieved September 19, 2023.

- ^ "Can we fight climate change by sinking carbon into the sea?". Canary Media. May 11, 2023. Retrieved September 19, 2023.

- ^ CO2 wettability of seal and reservoir rocks and the implications for carbon geo-sequestration - Iglauer - 2015 - Water Resources Research - Wiley Online Library

- ^ Morgan, Sam (September 6, 2019). "Norway's carbon storage project boosted by European industry". www.euractiv.com. Archived from the original on June 27, 2020. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- ^ a b Benson, S.M.; Surles, T. (October 1, 2006). "Carbon Dioxide Capture and Storage: An Overview With Emphasis on Capture and Storage in Deep Geological Formations". Proceedings of the IEEE. 94 (10): 1795–1805. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2006.883718. ISSN 0018-9219. S2CID 27994746. Archived from the original on June 11, 2020. Retrieved September 10, 2019.

- ^ Aydin, Gokhan; Karakurt, Izzet; Aydiner, Kerim (September 1, 2010). "Evaluation of geologic storage options of CO2: Applicability, cost, storage capacity and safety". Energy Policy. Special Section on Carbon Emissions and Carbon Management in Cities with Regular Papers. 38 (9): 5072–5080. Bibcode:2010EnPol..38.5072A. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2010.04.035.

- ^ Smit, Berend; Reimer, Jeffrey A.; Oldenburg, Curtis M.; Bourg, Ian C. (2014). Introduction to Carbon Capture and Sequestration. London: Imperial College Press. ISBN 978-1-78326-328-8.

- ^ Iglauer, Stefan; Pentland, C. H.; Busch, A. (January 2015). "CO2 wettability of seal and reservoir rocks and the implications for carbon geo-sequestration". Water Resources Research. 51 (1): 729–774. Bibcode:2015WRR....51..729I. doi:10.1002/2014WR015553. hdl:20.500.11937/20032.

- ^ "Carbon-capture Technology To Help UK Tackle Global Warming". ScienceDaily. July 27, 2007. Archived from the original on June 3, 2016. Retrieved February 3, 2023.

- ^ Phan, Anh; Doonan, Christian J.; Uribe-Romo, Fernando J.; Knobler, Carolyn B.; O'Keeffe, Michael; Yaghi, Omar M. (January 19, 2010). "Synthesis, Structure, and Carbon Dioxide Capture Properties of Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks". Accounts of Chemical Research. 43 (1): 58–67. doi:10.1021/ar900116g. ISSN 0001-4842. PMID 19877580. Archived from the original on February 22, 2023. Retrieved February 22, 2023.

- ^ Schuiling, Olaf. "Olaf Schuiling proposes olivine rock grinding". Archived from the original on April 11, 2013. Retrieved December 23, 2011.

- ^ Snæbjörnsdóttir, Sandra Ó.; Sigfússon, Bergur; Marieni, Chiara; Goldberg, David; Gislason, Sigurður R.; Oelkers, Eric H. (2020). "Carbon dioxide storage through mineral carbonation" (PDF). Nature Reviews Earth & Environment. 1 (2): 90–102. Bibcode:2020NRvEE...1...90S. doi:10.1038/s43017-019-0011-8. S2CID 210716072. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 4, 2022. Retrieved February 6, 2023.

- ^ McGrail, B. Peter; et al. (2014). "Injection and Monitoring at the Wallula Basalt Pilot Project". Energy Procedia. 63: 2939–2948. Bibcode:2014EnPro..63.2939M. doi:10.1016/j.egypro.2014.11.316.

- ^ Bhaduri, Gaurav A.; Šiller, Lidija (2013). "Nickel nanoparticles catalyse reversible hydration of CO2 for mineralization carbon capture and storage". Catalysis Science & Technology. 3 (5): 1234. doi:10.1039/C3CY20791A.

- ^ Wilson, Siobhan A.; Dipple, Gregory M.; Power, Ian M.; Thom, James M.; Anderson, Robert G.; Raudsepp, Mati; Gabites, Janet E.; Southam, Gordon (2009). "CO2 Fixation within Mine Wastes of Ultramafic-Hosted Ore Deposits: Examples from the Clinton Creek and Cassiar Chrysotile Deposits, Canada". Economic Geology. 104: 95–112. doi:10.2113/gsecongeo.104.1.95.

- ^ Power, Ian M.; Dipple, Gregory M.; Southam, Gordon (2010). "Bioleaching of Ultramafic Tailings by Acidithiobacillus spp. For CO2 Sequestration". Environmental Science & Technology. 44 (1): 456–62. Bibcode:2010EnST...44..456P. doi:10.1021/es900986n. PMID 19950896.

- ^ Power, Ian M; Wilson, Siobhan A; Thom, James M; Dipple, Gregory M; Southam, Gordon (2007). "Biologically induced mineralization of dypingite by cyanobacteria from an alkaline wetland near Atlin, British Columbia, Canada". Geochemical Transactions. 8 (1): 13. Bibcode:2007GeoTr...8...13P. doi:10.1186/1467-4866-8-13. PMC 2213640. PMID 18053262.

- ^ Power, Ian M.; Wilson, Siobhan A.; Small, Darcy P.; Dipple, Gregory M.; Wan, Wankei; Southam, Gordon (2011). "Microbially Mediated Mineral Carbonation: Roles of Phototrophy and Heterotrophy". Environmental Science & Technology. 45 (20): 9061–8. Bibcode:2011EnST...45.9061P. doi:10.1021/es201648g. PMID 21879741.

- ^ a b Herzog, Howard (March 14, 2002). "Carbon Sequestration via Mineral Carbonation: Overview and Assessment" (PDF). Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved March 5, 2009.

- ^ "Conference Proceedings". netl.doe.gov. Archived from the original on February 17, 2017. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- ^ Schuiling, R.D.; Boer, de P.L. (2011). "Rolling stones; fast weathering of olivine in shallow seas for cost-effective CO2 capture and mitigation of global warming and ocean acidification" (PDF). Earth System Dynamics Discussions. 2 (2): 551–568. Bibcode:2011ESDD....2..551S. doi:10.5194/esdd-2-551-2011. hdl:1874/251745. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 22, 2016. Retrieved December 19, 2016.

- ^ Le Page, Michael (June 19, 2016). "CO2 injected deep underground turns to rock – and stays there". New Scientist. Archived from the original on December 5, 2017. Retrieved December 4, 2017.

- ^ Proctor, Darrell (December 1, 2017). "Test of Carbon Capture Technology Underway at Iceland Geothermal Plant". POWER Magazine. Archived from the original on December 5, 2017. Retrieved December 4, 2017.

- ^ "The Ocean, a carbon sink - Ocean & Climate Platform". December 3, 2016. Retrieved May 21, 2024.

- ^ Heinze, C., Meyer, S., Goris, N., Anderson, L., Steinfeldt, R., Chang, N., ... & Bakker, D. C. (2015). The ocean carbon sink–impacts, vulnerabilities and challenges. Earth System Dynamics, 6(1), 327-358.

- ^ a b c IPCC, 2021: Annex VII: Glossary [Matthews, J. B. R., V. Möller, R. van Diemen, J. S. Fuglestvedt, V. Masson-Delmotte, C. Méndez, S. Semenov, A. Reisinger (eds.)]. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S. L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M. I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J. B. R. Matthews, T. K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 2215–2256, doi:10.1017/9781009157896.022.

- ^ Ortega, Alejandra; Geraldi, N.R.; Alam, I.; Kamau, A.A.; Acinas, S.; Logares, R.; Gasol, J.; Massana, R.; Krause-Jensen, D.; Duarte, C. (2019). "Important contribution of macroalgae to oceanic carbon sequestration". Nature Geoscience. 12 (9): 748–754. Bibcode:2019NatGe..12..748O. doi:10.1038/s41561-019-0421-8. hdl:10754/656768. S2CID 199448971. Archived from the original on May 6, 2021. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- ^ Temple, James (September 19, 2021). "Companies hoping to grow carbon-sucking kelp may be rushing ahead of the science". MIT Technology Review. Archived from the original on September 19, 2021. Retrieved November 25, 2021.

- ^ Flannery, Tim (November 20, 2015). "Climate crisis: seaweed, coffee and cement could save the planet". The Guardian. Archived from the original on November 24, 2015. Retrieved November 25, 2015.

- ^ Vanegasa, C. H.; Bartletta, J. (February 11, 2013). "Green energy from marine algae: biogas production and composition from the anaerobic digestion of Irish seaweed species". Environmental Technology. 34 (15): 2277–2283. Bibcode:2013EnvTe..34.2277V. doi:10.1080/09593330.2013.765922. PMID 24350482. S2CID 30863033.

- ^ a b Chung, I. K.; Beardall, J.; Mehta, S.; Sahoo, D.; Stojkovic, S. (2011). "Using marine macroalgae for carbon sequestration: a critical appraisal". Journal of Applied Phycology. 23 (5): 877–886. Bibcode:2011JAPco..23..877C. doi:10.1007/s10811-010-9604-9. S2CID 45039472.

- ^ Duarte, Carlos M.; Wu, Jiaping; Xiao, Xi; Bruhn, Annette; Krause-Jensen, Dorte (2017). "Can Seaweed Farming Play a Role in Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation?". Frontiers in Marine Science. 4: 100. doi:10.3389/fmars.2017.00100. ISSN 2296-7745.

- ^ Behrenfeld, Michael J. (2014). "Climate-mediated dance of the plankton". Nature Climate Change. 4 (10): 880–887. Bibcode:2014NatCC...4..880B. doi:10.1038/nclimate2349.

- ^ Mcleod, E.; Chmura, G. L.; Bouillon, S.; Salm, R.; Björk, M.; Duarte, C. M.; Silliman, B. R. (2011). "A blueprint for blue carbon: toward an improved understanding of the role of vegetated coastal habitats in sequestering CO2" (PDF). Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 9 (10): 552–560. Bibcode:2011FrEE....9..552M. doi:10.1890/110004. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved September 30, 2019.